The state of autonomous legislation in Europe

28 February 2019

28 February 2019

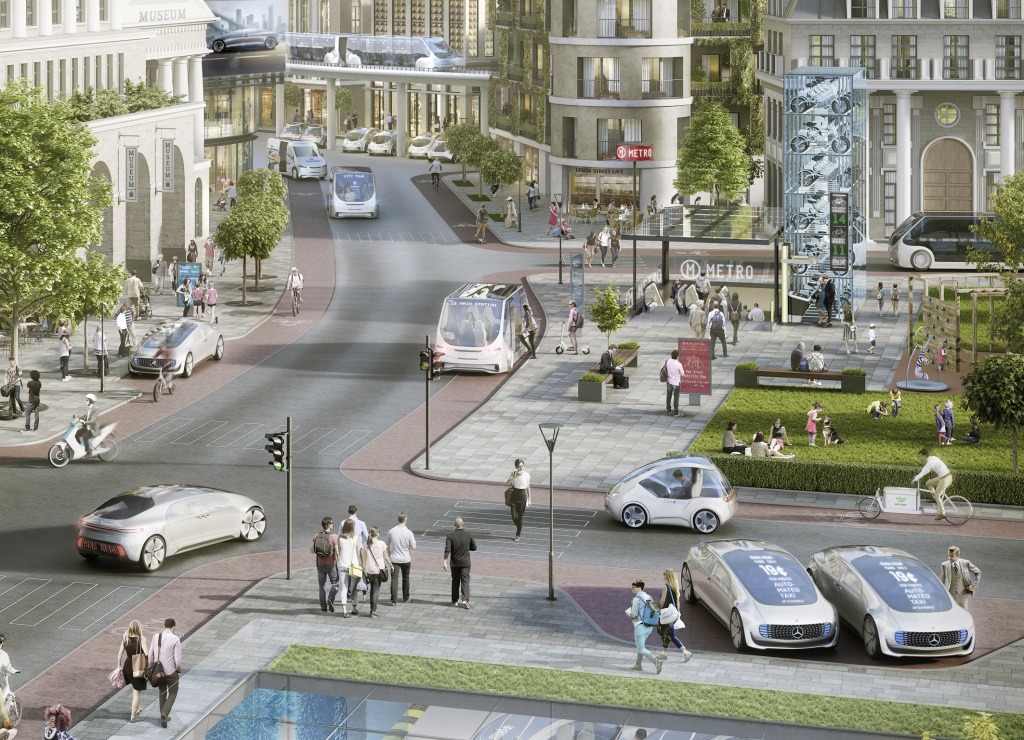

Manufacturers and technology companies across Europe are working to prepare autonomous vehicles for public use. Whether this is as part of a model launch or a mobility service, it is not a case of ′if’ driverless cars will be seen on the roads, but ′when’.

However, countries across the continent are all claiming that they want to be the ′leader’ in the field, developing the technology for both domestic use and to sell to vehicle manufacturers around the world. Carmakers are working together with governments and research institutions, while new start-ups are making the most of funding programs to play their part in a complicated technology.

There is, however, a lot of legislation to put in place to ensure that trials of autonomous cars can take place, let alone their sale. ′Autonomous and connected driving will not happen on its own, and we need to produce the right framework to simulate progress,’ states Carlos Moedas, European Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation. ′If you have 100 million cars that depend on fuel and less than one million electric cars on the roads, as we did five years ago, there is a big imbalance that highlights there is more to do to drive up their adoption and bring more manufacturers into the technology. Car manufacturers are in a worldwide race for automation, and it is one that Europe needs to win.’

The legislation conundrum will also lead to increased talks between EU member states, as vehicles are expected to drive on different countries’ road systems. For this to happen, countries need to align their programs. Some are at a more advanced stage, while others are testing in different areas.

The UK has set up a government department, the Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAV), and is working on legislation to allow testing on motorways in the country. There are also testing schemes in cities, including London and Coventry, with research organisations established to develop the technology and systems.

′Since 2014, the UK Government has helped to fund over 200 organisations to work collaboratively on over 70 projects,’ states Alan Nettleton, senior technologist at Transport Systems Catapult (TSC). ′These projects aim to provide a solution to a wide range of challenges related to connectivity, automation and feature many types of vehicles from small passenger-carrying pods to HGVs.’

TSC is a government-backed centre of excellence that has helped create and deliver ambitious and pioneering Connected and Autonomous Vehicle (CAV) projects in the UK. It is not only helping to deliver technology but supporting the development of infrastructure in the country.

′The recently updated Code of Practice for Automated Vehicle Trialling provides welcome further clarity on what is expected of organisations wishing to test autonomous vehicles on UK roads,’ Nettleton adds.

′It remains the responsibility of those carrying out trials to ensure that their trials comply with all relevant legal requirements. The difficulty arises when those legal requirements, which were not developed with autonomous vehicles in mind, are contradictory with their operation. This is why the Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission are undertaking a review of the legal framework on behalf of the UK Government’s Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles.’

In Germany, the Autonomous Vehicle Bill was enacted in June 2017, modifying the existing Road Traffic Act defining the requirements for highly and fully automated vehicles, while also addressing the rights of the driver.

The bill defines what a highly and fully autonomous vehicle is and states that such technology must comply with traffic regulations, recognise when the driver needs to resume control, and inform him or her with sufficient lead time as well as at any time permitting the driver to manually override or deactivate the automated driving mode.

Currently, autonomous testing legislation is handed out by city regulatory authorities. Some have approved pilot fleets operating on private property that serve as an example of wider adoption, including shuttle services interacting with pedestrians and bicycles. However, the current federal government plans to create an infrastructure suitable for Level 5 fully autonomous vehicles by the end of the legislative period. Germany also aims to expand autonomous vehicle testing on the autobahn beyond the A9 highway in Bavaria, where it is experimenting with vehicle-to-vehicle communication via 5G mobile networks.

France is establishing a legislative framework that will allow the testing of autonomous cars on public roads in 2019.

Level 4 vehicles, those with almost total autonomy, will be used on roads around the country with no human operator behind the wheel, as the current legislation requires. Currently, only certain companies can test driverless vehicles in the country, and while these are conducted on public roads, this is heavily restricted to time and location, to ensure there is no risk to ordinary members of the public.

The French Government is supporting the development of self-driving cars, with the aim of deploying ′highly automated’ vehicles on public roads between 2020 and 2022.

More than 50 autonomous-vehicle test projects have taken place in France since 2014, including robotaxis, buses and private vehicles. The government has made €40 million available to help subsidise new projects.

Spain is working to expand rules for self-driving vehicles, as well as adding modifications to insurance laws to offer an overall legal framework for the technology.

The regulation of autonomous-driving tests currently comes from an instruction approved in November 2015 by the Direccion General de Trafico (DGT). The rule encompasses all self-driving cars up to Level 5, which means full autonomy on all roads and under any conditions.

In January 2018, the DGT and technology company Mobileye agreed to a collaboration intended ′to reduce road accidents and prepare Spain’s infrastructure ecosystem and regulatory policy for the driving of autonomous vehicles.’

This project transforms Barcelona into a full-scale test laboratory by putting a 5,000-vehicle fleet in the city equipped with the Mobileye 8 Connect technology. Mobileye and the DGT will also collaborate on defining the regulatory roadmap required for an autonomous future.

Italy passed its first law regulating testing of autonomous vehicles in February last year. Activity will be permitted on ′specific roads’ provided the road operator authorises it, giving them final say over the testing procedure. Also, a supervisor will have to be able to take back control of the car at any time.

Carmakers and research centres will have to declare that the technology is fully ready for testing on the road to which it is assigned. This means factors such as painted lines, stop signs and traffic signals must be taken into account, as well as speed limits and restrictions. Tests have to be authorised by Italy’s Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, and vehicles need to be homologated in their original guise before use.