Insight: What options does the UK Government ban on traditional engines from 2040 leave for fleets?

30 January 2018

30 January 2018

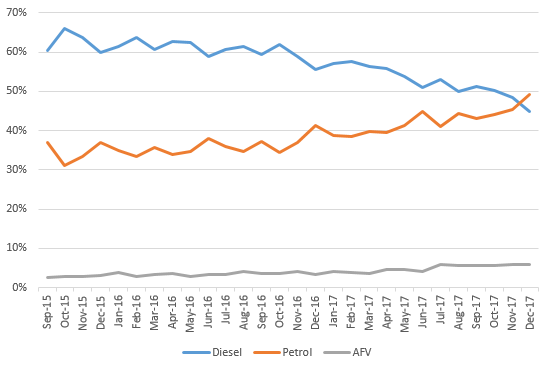

Although the diesel share of the entire UK new car market plummeted six percentage points from 48% in 2016 to 42% in 2017, diesel remained the leading powertrain for fleets according to SMMT registrations data on the fleet sales channel. However, even in this domain, the diesel share has been declining in the wake of the Dieselgate scandal which broke in September 2015 and lost seven percentage points compared to 2016, falling from 60% to a 53% share. Moreover, the diesel share of the fleet channel dropped below 50% in August, November and December and even fell below that of petrol cars in December 2017, capturing 45% share compared to 49% for petrol.

The majority of the defection from diesel has been to petrol cars, which gained six percentage points of share in 2017, climbing from 36% in 2016 to 42% in 2017. The remaining one percentage point loss in the diesel share was predominantly gained by petrol-electric hybrids, with pure electric vehicles capturing just 0.3% of all UK fleet registrations in 2017, albeit up from 0.2% in 2016.

Fleet registrations by fuel type, UK, September 2015 to December 2017

Although diesel will invariably continue to lose share in fleet sales for the foreseeable future, buyers will predominantly defect to petrol cars. Nevertheless, diesel does remain the most cost-effective solution for fleet vehicles which cover higher mileages, even though the UK is the only one of the big five West European markets where diesel costs more at the pump than petrol.

In 2017, alternative fuel vehicles (AFV), comprising hybrid and pure electric, commanded just a 4.9% share of fleet demand. Although this increased from 3.5% in 2016, the AFV uptake remains lower in fleets than amongst private buyers, and so challenging times are ahead with the UK Government aiming to ban the sale of cars with petrol and diesel engines by 2040.

Electric vehicles will not gain significant share until they become more financially competitive and the charging network is sufficiently developed to allay range anxiety. As to which powertrains will prevail in the long term depends on the industry offering (Toyota has recently announced plans to stop the sale of diesel cars in Italy and France for example) and the legislative environment. Given the recently confirmed rise in CO2 emissions in the UK in 2017, it is even possible that UK Government policy will turn to promoting the latest clean diesels as a solution until electric vehicles and, in the longer term, hydrogen cars become more financially viable.

On the subject of the charging infrastructure, it is noteworthy that the UK Government is aiming for the majority of cars to already be electric in 2030 while news has also broken that only five UK councils have taken advantage of the Government’s grant for charging points. There is still a chicken and egg situation, whereby the lack of charging points is holding back demand for electric vehicles, which in turn renders investment in charging points rather unattractive.

The proposed ban on the sale of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles from 2040 sends a clear message that the future lies with hybrid, electric and/or hydrogen vehicles but simply banning petrol and diesel vehicles will not have the desired effect without the costs of these vehicles being reduced. This, therefore, leaves policymakers with only three choices to achieve their aim; subsidise low-emission cars, penalise petrol and diesel cars, or do both.

The 2040 timeframe is in line with similar plans announced by the French Government and is actually rolling out later than plans to ban petrol and diesel cars announced in other European markets. Given this, the timeframe is realistic, but a concerted international effort is required, or at least lessons will need to be learned from other countries as to which measures are effective and which are not in order to achieve the aim of pollution-free motoring.

Although the proposed 2040 ban on cars which only feature petrol or diesel engines in the UK sends the message that non-conventional powertrains are the future, it cannot be seen as a victory for electric cars specifically unless the charging infrastructure is sufficiently developed to increase their demand, which in turn would reduce their costs as economies of scale kick in. There are indeed also concerns about whether electricity grids can cope with the additional demand but electricity for cars could be offered at a cheaper rate at night than during the day when the demands on the grid are naturally higher. Technology solutions such as bi-directional charging – which returns electricity to the grid and/or powers the car owner’s home – would also help to relieve the burden.

Ultimately, however, prohibitive costs, range anxiety, long charging times, limited resources of raw materials needed for batteries (such as lithium) and the question of the grid generating sufficient electricity may continue to limit the uptake of electric vehicles indefinitely, especially in the fleet domain. Other powertrains such as hydrogen, which could be delivered through the existing fuel retail network and offers quicker refuelling times than recharging a battery, may yet prove to be the long-term solution.