SMMT sets out steps for success in UK electric transition

30 June 2021

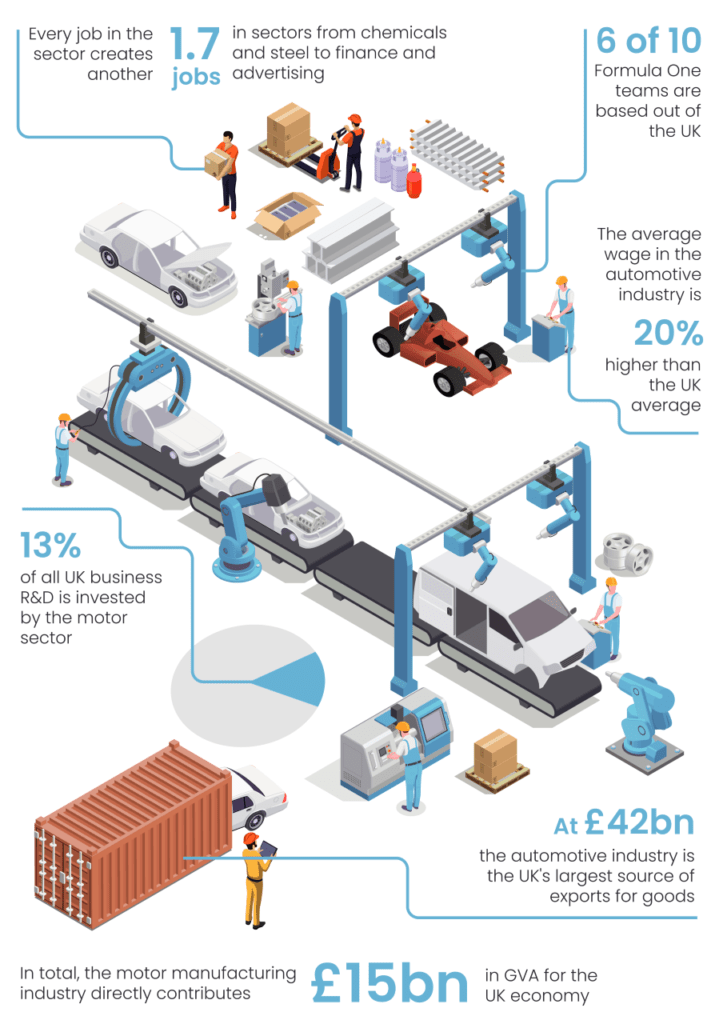

The UK automotive industry needs government support to secure jobs and investment as it looks towards an electric future. This is the finding of a new report commissioned by the country’s Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) and which it presented at its annual summit on 29 June, 2021.

With the UK introducing a ban on the sale of new internal-combustion engine (ICE) models in 2030, the body believes that now is the time for action to secure the market. In addition, with COVID-19 heavily impacting the sector, the SMMT is calling for help to ‘build back better’.

There are fears that if no action is taken, the country could fall behind others in the race to electrify. This would also include manufacturing, where battery gigafactories are critical to secure vehicle production in the UK.

‘The next few years represent a critical period for the sector,’ commented Mike Hawes, chief executive of the SMMT. ‘The pace of technological change is accelerating and the competition more ferocious. If we are to secure vehicle manufacturing in this country, with all the benefits to society that it brings, decisions need to be made today. The automotive sector is uniquely placed to help this government deliver on its agenda; to level up, deliver net-zero and trade globally. The government has made clear its support for the sector in its negotiations with Europe, so now is the time to go full throttle and take bold action to support one of Britain’s most important industries.’

The report, Full Throttle: Driving UK Automotive Competitiveness, sets out a series of policy proposals for this year and the remainder of the decade. It calls for a new ‘Build Back Better Fund’ to support industry transformation. This includes funding for other manufacturing sectors to help revolutionise production lines and overcome some of the areas where the UK lags in cost competitiveness or strategic support – from skills to energy costs. Most importantly, the fund will help the sector transition to net-zero.

Gigafactories needed

Recently, carmakers across Europe have been announcing new partnerships to build gigafactories near existing manufacturing lines. These arrangements allow companies to shorten supply chains and reduce carbon footprints in line with commitments to net-zero production. Building locally reduces the need for lithium-ion cell shipping and cuts down on the number of heavy-goods vehicles (HGVs) needed to carry them to plants.

Unlike other major governments, the UK has yet to back its electric ambition with a matching level of investment in battery-production incentives, charging networks and affordable clean energy. According to the SMMT, independent analysts predict that by 2025, the UK will have just 12GWh of lithium-ion battery capacity, compared to 164GWh in Germany, 91GWh in the US or 32GWh in France.

The UK is home to a number of vehicle-manufacturing plants, so the SMMT is calling for help to make the transition to battery manufacturing. Its report compiles four scenarios, from best to worst case:

- Central: The UK builds 60GWh of gigafactory supply by 2030, ensuring that it has ample battery supply to maintain current production volume, and offers significantly more generous incentives for business investment. Under this scenario, gross value added (GVA) and jobs return to a steady growth trajectory.

- Optimistic. The UK builds 80GWh, undertakes an ambitious programme of trade deals, and significantly improves its attractiveness for business investment. This sees GVA grow by around a third faster than in the central scenario and sees the sector as a whole gain around 40,000 jobs.

- Pessimistic. The UK only builds 30GWh of gigafactory supply, while non-tariff barriers with the EU moderately increase from the middle of the decade. Under this scenario, GVA recovers from COVID-19 and then largely stagnates, with substantial jobs lost over time.

- Stranded. The UK only builds one additional gigafactory, leaving total supply under 15GWh and failing to transition away from ICEs. As a result, around 90,000 jobs are lost, with the majority of these concentrated outside of London and the South East, further increasing regional inequality.

The biggest issue is that carmakers will move their production facilities away from the UK and to the European mainland, where they can take advantage of gigafactories that are planned for development.

‘There is a risk [of moving manufacturing outside the UK], batteries are big and heavy items to transport across Europe,’ said Michael Straughan, chief operating officer at Aston Martin Lagonda. ‘I would prefer to be in a position where the UK government, together with battery manufacturers, decides to protect our industry. We need four or five gigafactories in order to make this industry prosper in the UK.’

‘It will come down to cost. Batteries are very heavy items, and the further you have to transport them, the higher the costs will be,’ added Ruth Nic Aoidh, executive director of purchasing, SQA, commercial, government affairs and legal, McLaren Automotive.

Hydrogen society

The SMMT is also calling for the government to establish a hydrogen fuel-cell gigafactory with a 2GWh capacity to support cars, heavier vehicles and rail units by 2030. This plant would help to explore the usefulness of hydrogen in the automotive and other sectors as an alternative to battery propulsion. It would be capable of supplying the production of 17,000 cars, trucks, buses and trains.

Governments always talk about technology neutrality, but by setting the timetable so tough it is more or less dictating for the short to medium term, that it has to be electrification.’

Mike Hawes, chief executive, SMMT

However, while the UK government is keen to promote hydrogen, the push toward battery-electric propulsion and the tight deadlines for the end of ICE sales have tipped the development scales away from the fuel.

‘There is a role for hydrogen. Most obviously, it probably lends itself to heavier vehicles, obviously commercial vehicles in particular,’ said Hawes, in response to a question from Autovista24. ‘But I think that the challenge to much of the industry, as we see in the UK, is that we have got to achieve 100% zero-emission vehicles by 2030. In any industry, that is an incredibly short period. Electrification lends itself more readily to commercialisation at that scale by that time.

‘That is not to say other options should be ignored. Governments always talk about technology neutrality, but by setting the timetable so tough it is more or less dictating for the short to medium term, that it has to be electrification.’

‘I believe it is part of the future for passenger cars, maybe in the bigger passenger-car vehicles,’ added Michael Cole, president and chief executive of Hyundai Motor Europe. ‘But the timeframe we have to work with them both in the UK and in Europe, to become carbon neutral, does play a part in our decisions on technology development. I think we cannot put all of our eggs into the one basket of battery-electric vehicles, so we see that these technologies can very neatly sit alongside each other. So yes, hydrogen is something that we will continue to invest in, not only from the truck and other transport points of view, but also for passenger cars.’

Alison Jones, UK group managing director and senior vice president at Stellantis, added: ‘We are investing in hydrogen. In terms of its development, we are running trials with light-commercial vehicles and want to expand these into the UK. It is important when considering the technology that we develop green hydrogen, and you also need the infrastructure to support it. So, you come back to the same challenges that we have with electric technology, but by doing these pilots and these trials, you find out what is possible and how you can then adapt it and use it for the future.’

Consumer confidence

When it comes to securing the future of the UK automotive industry, the consumer is key. If cars are not sold, then profits drop and both investment and jobs are lost. However, convincing the majority of the public to switch to a new propulsion technology in eight-and-a-half years is a big challenge.

To aid this, the SMMT suggests that the government needs to continue the ‘plug-in vehicle incentives’ beyond their current term and exempt ultra-low-emission vehicles (ULEVs) from taxation for the next five years. A short-term tax exemption, including from VAT, as well as extending consumer and fleet incentives. This would help bridge the gap until ULEVs can reach total cost of ownership (TCO) parity on their own and bring the country in line with incentive levels in other markets.

The government should also develop an infrastructure strategy to ensure that at least 2.3 million public-charging points are in place by 2030. Public support is likely to be particularly important to deliver additional on-street charge points (1.95 million required) and ensure that less prosperous country areas do not get left behind.

There also needs to be an independent review to holistically consider the long-term future of fuel, vehicle and road-based taxes in a decarbonised market. The industry body states that consumers should not be surprised by sudden tax shifts down the line, especially as the government is calling for the switch to be made. Any additional and unknown taxes would mirror similar problems with diesel, which the UK government once heavily promoted but, in recent years, has been hit with increases in vehicle-excise duty (VED), pricing the technology out of the reach of many drivers.

The full report outlines several other key areas to which the UK needs to commit to ensure its push for a zero-carbon automotive industry is a success. However, it is clear that decisions need to be taken now. Otherwise, the consequences for the country’s market may be dire.