Swedish ICE ban would not drastically aid climate targets

28 May 2021

A rapid and mandatory phasing in of electrically-chargeable vehicles (EVs) in Sweden will benefit the climate, but only once the entire car parc has completed the transition.

The Chalmers University of Technology has released the findings of a scientific study into how any internal combustion engine (ICE) ban would affect emissions in the country. The Swedish government has proposed a ban to come into force in 2030, but the report suggests this alone will not be enough to meet climate targets.

′The lifespan of the cars currently on the roads and those which would be sold before the introduction of such a restriction mean that it would take some time – around 20 years – before the full effect becomes visible,’ says Johannes Morfeldt, researcher in Physical Resource Theory at Chalmers University of Technology and lead author of the recently-published study.

Parc problem

While countries are looking at ICE bans to help lower pollution, the study highlights post-implementation issues. Restricting sales only eliminates part of the problem, as there will still be millions of petrol and diesel vehicles still on the roads. Depending on the average age of the car parc, it could take many more years after a sales ban before all vehicles are zero-emission.

As an example, the UK will ban the sale of petrol and diesel vehicles in 2030. However, the latest car-parc analysis by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) suggests the average age of a car in the UK is 8.4 years. Additionally, 27.9% of the parc is over 12 years old. Therefore, it may not be until 2042 that a vast majority of UK vehicles are non-ICE. Of course, drivers may decide to hold on to their vehicles for longer rather than switch to zero-emission options, which may drive up the parc’s average age.

For Sweden to reach its climate-change goals, the government would need to implement its ICE ban by 2025. If it decides to continue on the path to 2030, the study suggests that the use of biofuels in petrol and diesel needs to increase significantly. Only then could the country achieve targets for passenger vehicles outlined in its ′reduction obligation‘

Source: Yen Strandqvist/Chalmers University of Technology

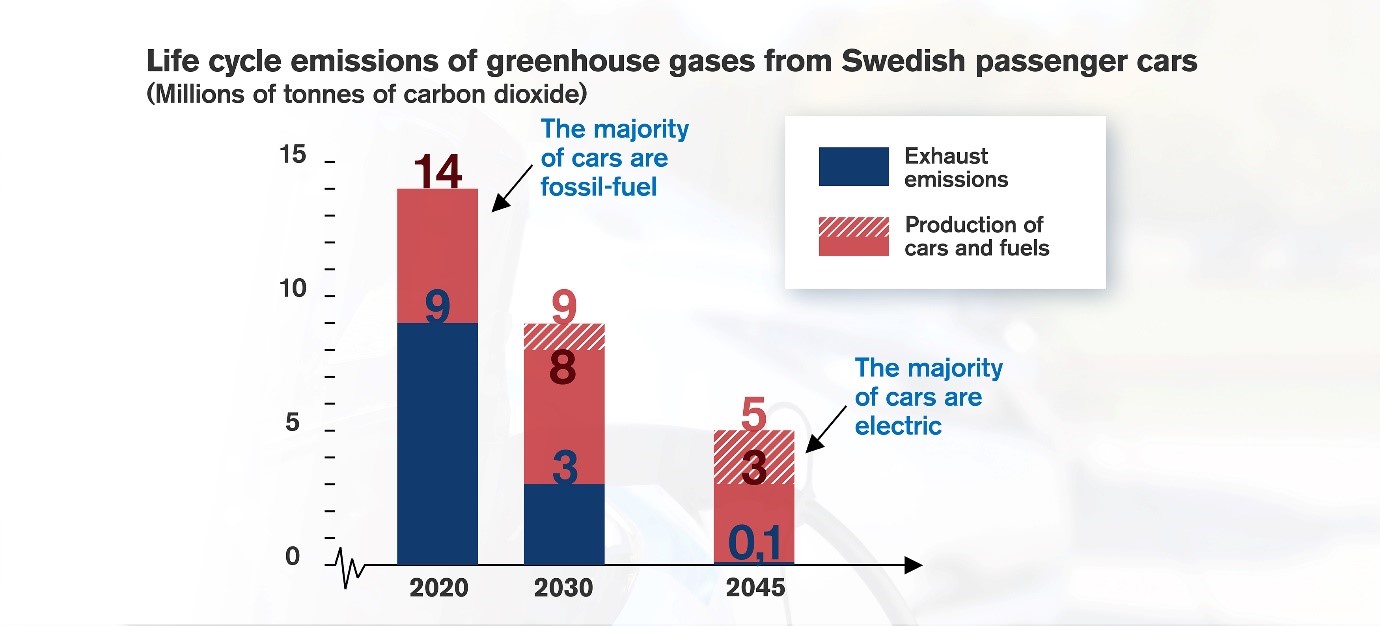

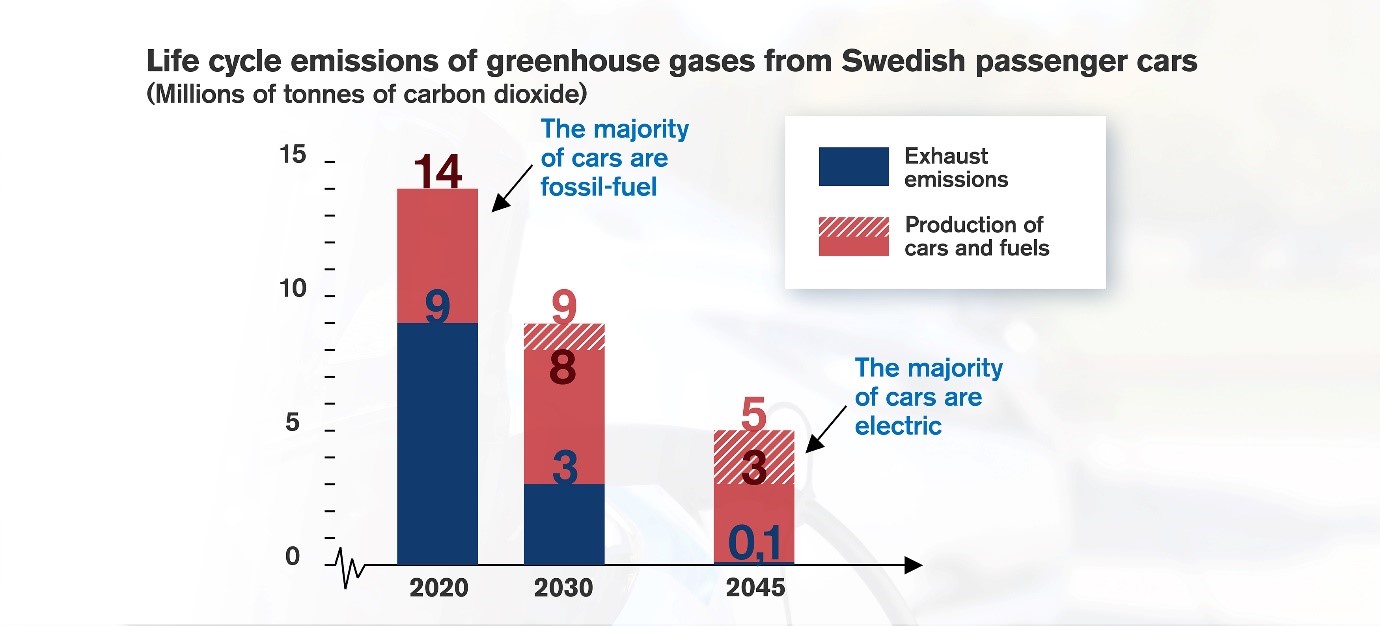

′The results from our study show that rapid electrification of the Swedish car fleet would reduce life-cycle emissions, from 14 million tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2020 to between three and five million tonnes by the year 2045. The end result in 2045 will depend mainly on the extent to which possible emission reductions in the industry are realised,’ added Morfeldt.

Battery emissions

A transition from petrol and diesel cars to electric cars will mean an increased demand for batteries. Batteries for electric cars are often criticised, not least for the fact that they result in high levels of greenhouse-gas emissions during manufacture.

′There are relatively good opportunities to reduce emissions from global battery manufacturing,’ commented Morfeldt. ′Our review of the literature on this shows that average emissions from global battery manufacture could decrease by about two thirds per kilowatt hour of battery capacity by the year 2045. However, most battery production takes place overseas, so Swedish decision-makers have more limited opportunities to influence this.’

The study indicates that, from a climate perspective, it does not matter where the emissions take place. Instead, the risk with decisions taken at a national level for lowering passenger-vehicle emissions is that they could lead to increased emissions elsewhere – a phenomenon sometimes termed ′carbon leakage’. In this case, the increase in emissions would come from greater demand for batteries.

In that case, the Swedish decision to ban ICE vehicles would not have as great an effect on reducing the climate impact as desired. The lifecycle emissions would end up in the upper range – around five million tonnes of carbon dioxide instead of around three million tonnes. Due to this, there may be reason to regulate vehicle and battery-production emissions from a lifecycle perspective.

′Within the EU, for example, there is a discussion about setting a common standard for the manufacture of batteries and vehicles – in a similar way as there is a standard that regulates what may be emitted from exhausts,’ added Morfeldt.

′But, given Sweden’s low emissions from electricity production, a ban on sales of new fossil-fuel cars would indeed result in a sharp reduction of the total climate impact, regardless of how the industry develops.’

Source: Yen Strandqvist/Chalmers University of Technology

′The results from our study show that rapid electrification of the Swedish car fleet would reduce life-cycle emissions, from 14 million tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2020 to between three and five million tonnes by the year 2045. The end result in 2045 will depend mainly on the extent to which possible emission reductions in the industry are realised,’ added Morfeldt.

Battery emissions

A transition from petrol and diesel cars to electric cars will mean an increased demand for batteries. Batteries for electric cars are often criticised, not least for the fact that they result in high levels of greenhouse-gas emissions during manufacture.

′There are relatively good opportunities to reduce emissions from global battery manufacturing,’ commented Morfeldt. ′Our review of the literature on this shows that average emissions from global battery manufacture could decrease by about two thirds per kilowatt hour of battery capacity by the year 2045. However, most battery production takes place overseas, so Swedish decision-makers have more limited opportunities to influence this.’

The study indicates that, from a climate perspective, it does not matter where the emissions take place. Instead, the risk with decisions taken at a national level for lowering passenger-vehicle emissions is that they could lead to increased emissions elsewhere – a phenomenon sometimes termed ′carbon leakage’. In this case, the increase in emissions would come from greater demand for batteries.

In that case, the Swedish decision to ban ICE vehicles would not have as great an effect on reducing the climate impact as desired. The lifecycle emissions would end up in the upper range – around five million tonnes of carbon dioxide instead of around three million tonnes. Due to this, there may be reason to regulate vehicle and battery-production emissions from a lifecycle perspective.

′Within the EU, for example, there is a discussion about setting a common standard for the manufacture of batteries and vehicles – in a similar way as there is a standard that regulates what may be emitted from exhausts,’ added Morfeldt.

′But, given Sweden’s low emissions from electricity production, a ban on sales of new fossil-fuel cars would indeed result in a sharp reduction of the total climate impact, regardless of how the industry develops.’

Source: Yen Strandqvist/Chalmers University of Technology

′The results from our study show that rapid electrification of the Swedish car fleet would reduce life-cycle emissions, from 14 million tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2020 to between three and five million tonnes by the year 2045. The end result in 2045 will depend mainly on the extent to which possible emission reductions in the industry are realised,’ added Morfeldt.

Battery emissions

A transition from petrol and diesel cars to electric cars will mean an increased demand for batteries. Batteries for electric cars are often criticised, not least for the fact that they result in high levels of greenhouse-gas emissions during manufacture.

′There are relatively good opportunities to reduce emissions from global battery manufacturing,’ commented Morfeldt. ′Our review of the literature on this shows that average emissions from global battery manufacture could decrease by about two thirds per kilowatt hour of battery capacity by the year 2045. However, most battery production takes place overseas, so Swedish decision-makers have more limited opportunities to influence this.’

The study indicates that, from a climate perspective, it does not matter where the emissions take place. Instead, the risk with decisions taken at a national level for lowering passenger-vehicle emissions is that they could lead to increased emissions elsewhere – a phenomenon sometimes termed ′carbon leakage’. In this case, the increase in emissions would come from greater demand for batteries.

In that case, the Swedish decision to ban ICE vehicles would not have as great an effect on reducing the climate impact as desired. The lifecycle emissions would end up in the upper range – around five million tonnes of carbon dioxide instead of around three million tonnes. Due to this, there may be reason to regulate vehicle and battery-production emissions from a lifecycle perspective.

′Within the EU, for example, there is a discussion about setting a common standard for the manufacture of batteries and vehicles – in a similar way as there is a standard that regulates what may be emitted from exhausts,’ added Morfeldt.

′But, given Sweden’s low emissions from electricity production, a ban on sales of new fossil-fuel cars would indeed result in a sharp reduction of the total climate impact, regardless of how the industry develops.’

Source: Yen Strandqvist/Chalmers University of Technology

′The results from our study show that rapid electrification of the Swedish car fleet would reduce life-cycle emissions, from 14 million tonnes of carbon dioxide in 2020 to between three and five million tonnes by the year 2045. The end result in 2045 will depend mainly on the extent to which possible emission reductions in the industry are realised,’ added Morfeldt.

Battery emissions

A transition from petrol and diesel cars to electric cars will mean an increased demand for batteries. Batteries for electric cars are often criticised, not least for the fact that they result in high levels of greenhouse-gas emissions during manufacture.

′There are relatively good opportunities to reduce emissions from global battery manufacturing,’ commented Morfeldt. ′Our review of the literature on this shows that average emissions from global battery manufacture could decrease by about two thirds per kilowatt hour of battery capacity by the year 2045. However, most battery production takes place overseas, so Swedish decision-makers have more limited opportunities to influence this.’

The study indicates that, from a climate perspective, it does not matter where the emissions take place. Instead, the risk with decisions taken at a national level for lowering passenger-vehicle emissions is that they could lead to increased emissions elsewhere – a phenomenon sometimes termed ′carbon leakage’. In this case, the increase in emissions would come from greater demand for batteries.

In that case, the Swedish decision to ban ICE vehicles would not have as great an effect on reducing the climate impact as desired. The lifecycle emissions would end up in the upper range – around five million tonnes of carbon dioxide instead of around three million tonnes. Due to this, there may be reason to regulate vehicle and battery-production emissions from a lifecycle perspective.

′Within the EU, for example, there is a discussion about setting a common standard for the manufacture of batteries and vehicles – in a similar way as there is a standard that regulates what may be emitted from exhausts,’ added Morfeldt.

′But, given Sweden’s low emissions from electricity production, a ban on sales of new fossil-fuel cars would indeed result in a sharp reduction of the total climate impact, regardless of how the industry develops.’