Why automotive industry collaboration is important – and essential

31 July 2019

31 July 2019

By Phil Curry

The automotive industry is being reactive, rather than proactive, for the first time in decades. External pressures are forcing expensive development programmes for which no carmaker was fully prepared. With this in mind, we are starting to see a new industry era – that of close collaboration.

In the last four years, a chain of events has led to a new automotive world – one where electric and autonomous vehicles are crucial to secure the future while falling sales and changing attitudes towards vehicle ownership are creating pressure over sales and mobility services.

Partnering up

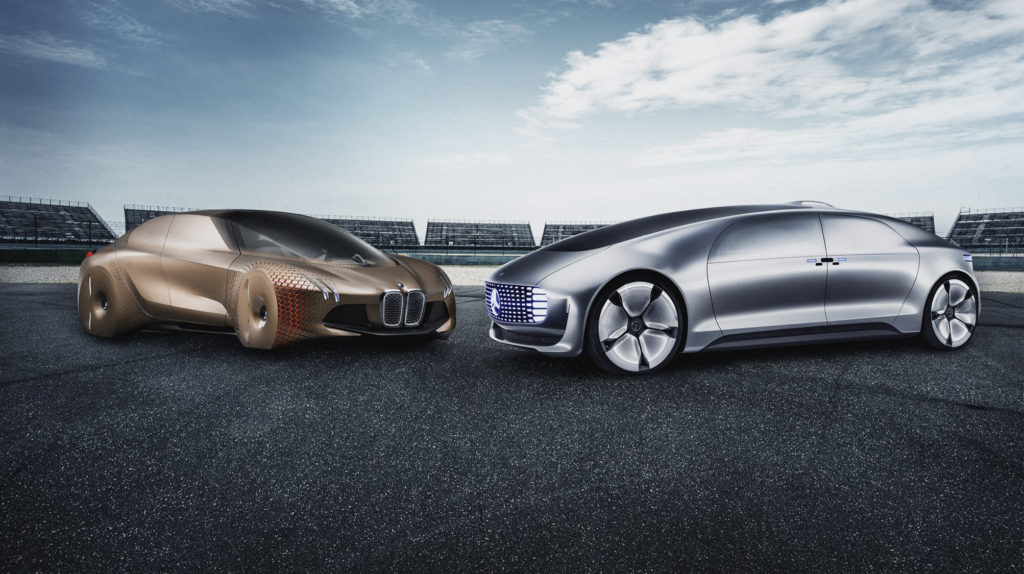

Ford is now working with the Volkswagen Group (VW) on electric vehicles (EVs), autonomous systems and commercial vehicles, while BMW and Daimler, once great rivals, are collaborating on autonomous technology and mobility services.

Toyota is partnering with Suzuki and Subaru to develop EVs and vehicles for new markets, and Renault has been working with Nissan for a number of years. The French carmaker was also looking likely to merge with Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA) until external forces made the deal untenable.

Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) is also working with BMW on EV technology, specifically drivetrains, while BMW is also working with FCA and several technology companies on driverless software.

All of this might have been unthinkable half a decade ago. The way the market has changed in such a short space of time means that if carmakers do not start to work together, they could be left behind.

Starting point

The Dieselgate scandal in 2015 can be seen as the catalyst. Until that time, diesel had a good reputation as a clean fuel, due to its low CO2 output. However, following the emergence of reports from the US over cheat devices being fitted to amend nitrogen oxide (NOx) levels in testing, the diesel market started to decline.

Suddenly, air pollution, rather than simple CO2 emissions, became a hot topic. Cities started to ban diesels and governments started to tax them heavily. The result is the collapse of the diesel market, especially in the last couple of years.

If you consider European CO2 targets, which have been active since 2009, for many carmakers, diesel was the ′lifeboat’ – the technology that would get it through. For many, sales of the technology outstripped petrol, meaning average CO2 emissions would be low, and if any fines were levied, they would be miniscule. Now petrol is dominating, that lifeboat is gone.

To add to the complication, the introduction of WLTP, due in part to the Dieselgate scandal, has pushed average CO2 emissions up even further.

Go electric

By the end of 2021, a manufacturer’s fleet must emit no more than 95g/km of CO2. Carmakers face a fine of €95 per gram over this limit, multiplied by the number of cars it sells in 2020 and 2021. For some, this could amount to billions of euros.

The only viable technology to counter rising CO2 levels is electric. Many carmakers have been working on the technology in the background, perhaps to launch a vehicle powered by batteries at some point. It is far more developed than hydrogen and battery electric vehicles (BEVs) wipe away CO2 numbers from fleets, bringing down average emissions and reducing potential fines.

The problem is the cost of this development. What may have been a trickle of R&D is now a big programme as carmakers rush to get battery technology ready to reduce CO2 levels. Many will not achieve it by 2021 and with stricter targets for 2025 and 2030, they have to ensure they do not face even bigger financial penalties in the future.

Autonomous development

Alongside all this is the development of autonomous vehicles. Once considered a ′folly’ and something that might be nice for a science fiction movie, the industry is facing competition from external sources, namely technology companies. Apple, Google, Uber and Lyft are all working on driverless vehicles and so if the automotive industry is not to fall behind, it too must develop systems.

The investment needed in autonomous driving is huge. For some carmakers, they have partnered with technology firms to remain relevant. Others have bought chip manufacturers, software companies or sensor businesses to advance their research. Changing ownership trends are also forcing their hand – with car-sharing becoming more popular, hailing an autonomous car will be the mobility choice of the future for the next generation.

Collaboration needed

So many outside influences occurring at once have pushed the industry into a reactive state. Technology must be developed, and must be done so quickly, or the financial penalties of fines and lost sales will be huge.

The cost of developing such systems is also huge. For example, in EV development, carmakers must source battery supplies, materials, develop new platforms and powertrains from scratch. With no battery production facilities in Europe, production and shipping from Asia have to be factored in as well. Sales of EVs account for a small percentage of the global market at present, however, so instant reward is unlikely.

The same goes for autonomous systems. Therefore, it is better for carmakers to share the burden.

By collaborating, companies can get what they want much quicker for half the cost. It is the adage ′two heads are better than one’ in this respect. It works even better when companies that are more advanced in different fields come together – take VW and Ford for example. The German manufacturer is advanced with its MEB EV platform, a technology area that Ford lacks in, while the US giant owns its own autonomous software company, an area where VW is behind.

Collaboration makes sense and it is almost certain that we have not seen the last announcement of two carmakers coming together. Ford and VW are open to more manufacturers joining their alliance, as are BMW and Daimler in their autonomous partnership. All of this heralds the start of a new era for the automotive industry as traditional rivalries make way to foster new relationships – for the good of new markets and even the world itself.