Will car sharing get a post-COVID second wind?

27 November 2020

27 November 2020

The sharing economy and car sharing are sociologically attractive concepts. We seek to live more sustainably, and digitally-enabled business models have increased accessibility to sharing solutions. On the other hand, car sharing (and ride hailing) have failed to reduce road congestion or the number of cars in operation. They share another joint challenge: they struggle to become profitable and have been crushed through the pandemic. Dr. Christof Engelskirchen, Autovista Group chief economist, shares his perspective.

The sharing economy is driven by a desire to connect with a community, to declutter, to increase flexibility and to live more sustainably. It is often facilitated by community-based online platforms. Car sharing is a logical extension of the sharing economy and has grown in popularity over the past 10 years. We differentiate between three types:

Ride hailing increases congestion

Ride-hailing businesses are struggling with profitability. There are concerns about the sustainability of the business model as long as cars need a driver. A scientific study from 2019, which analyses the role of ride-hailing companies on traffic congestion in San Francisco, concluded that ride hailing increases congestion. There is some substitution between ride hailing and other road trips, but most road trips add new cars to the road. Ride-hailing vehicles stopping at the curb to pick up or drop off passengers have a notable disruptive effect on traffic flow, especially on major arterials. This was evident at the CES in Las Vegas in 2019: the city lacks a solid public-transport infrastructure and if you choose to take an Uber or Lyft, signs direct you to pick-up and drop-off areas at the major resorts. Downtown, no curb pick-ups and drop-offs are permitted.

Unmet promise

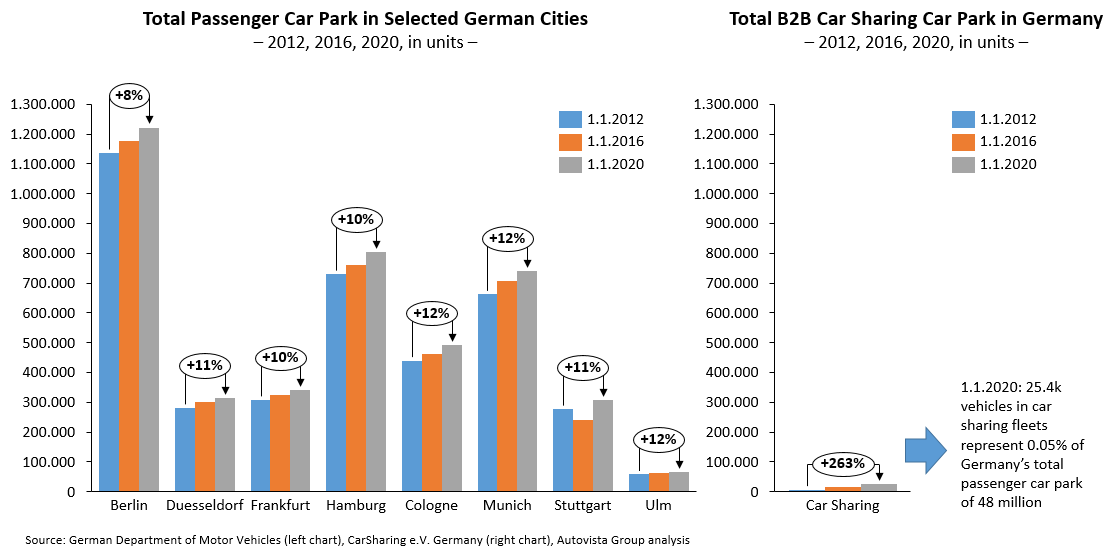

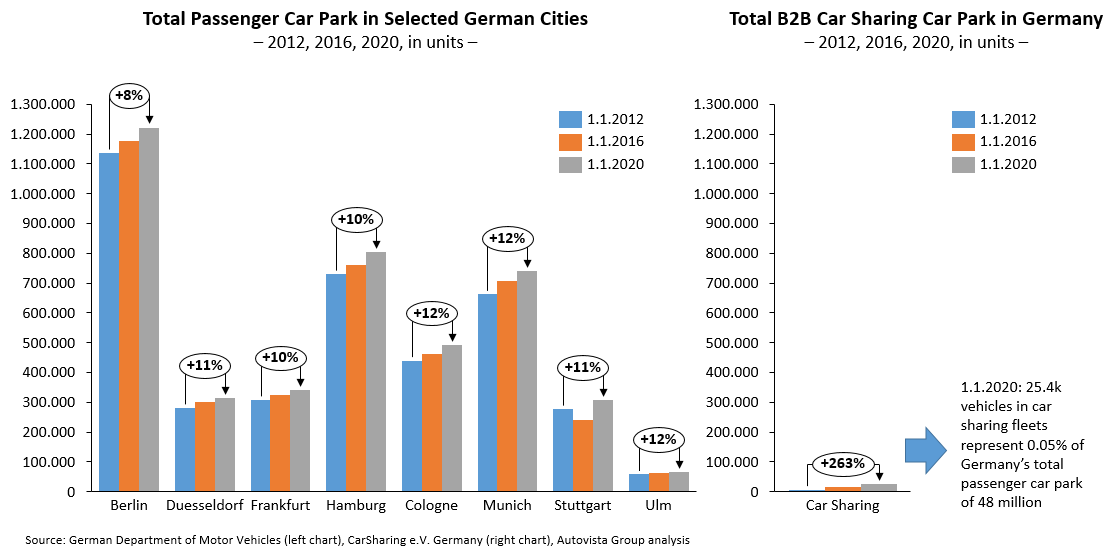

Car sharing has failed to deliver against the promise of contributing to lowering the traffic problems in big cities. It does not reduce the number of vehicles. It takes up parking space. It cannibalises public transport and cities will not give preferential treatment to these services unless they see a positive benefit. Stationary car sharing is less affected by these challenges but is also far less flexible for users. Many free-floating car-sharing services have been taken off the market because of profitability challenges, not only because of the lack of economies of scale.

Even Daimler and BMW, which combined their Car2Go and DriveNow services into ShareNow, have withdrawn from major cities and countries (e.g. Florence, London, Milan, Brussels and North America). Free-floating car sharing will likely continue to be part of multi-modal mobility solutions in the future, but there will be no or only very few additional cities added to the portfolio in the short term due to the challenges around profitability. Free-floating car sharing will not be a disruptive force to inner-city mobility. It will be a niche play, if it can be operated profitably.

The outlook

Stationary car sharing will continue to complement multi-modal mobility. With the current trend towards flexible work arrangements, suburban areas regain attractiveness. Stationary car-sharing services may add further value for those areas. Peer-to-peer offers have grown through the pandemic as people continue to avoid public transport. Retail locations, or car dealers, may find a niche to offer such services. Rental companies could also enter the market with shorter-term, more flexible arrangements.

Peer-to-peer ride hailing will continue to operate successfully in a niche. Professional-service ride hailing (e.g. Uber, Lyft) will continue to face profitability challenges. Ride hailing in its current form adds price pressure on the backs of drivers that are often self-employed.

In the medium term, professional-service ride hailing could benefit from autonomous driving Level 4, as this will replace the driver. Within the next five to 10 years, it may be suitable for very specific high-utilisation cases as the technology is very expensive. It will not be used in mixed-traffic situations any time soon, due to safety and liability concerns. An example could be autonomous ride hailing to bring people from a Park’n’Ride area to an out-of-city access point for existing public-transport infrastructure. Cities that rely on a highly-utilised public-transport infrastructure will not allow Waymo and other operators to take up and load off passengers at inner-city access and switchover points for public transport. The reason is that cities need to scale and increase utilisation of public transport and to manage car traffic.

Ride hailing increases congestion

Ride-hailing businesses are struggling with profitability. There are concerns about the sustainability of the business model as long as cars need a driver. A scientific study from 2019, which analyses the role of ride-hailing companies on traffic congestion in San Francisco, concluded that ride hailing increases congestion. There is some substitution between ride hailing and other road trips, but most road trips add new cars to the road. Ride-hailing vehicles stopping at the curb to pick up or drop off passengers have a notable disruptive effect on traffic flow, especially on major arterials. This was evident at the CES in Las Vegas in 2019: the city lacks a solid public-transport infrastructure and if you choose to take an Uber or Lyft, signs direct you to pick-up and drop-off areas at the major resorts. Downtown, no curb pick-ups and drop-offs are permitted.

Unmet promise

Car sharing has failed to deliver against the promise of contributing to lowering the traffic problems in big cities. It does not reduce the number of vehicles. It takes up parking space. It cannibalises public transport and cities will not give preferential treatment to these services unless they see a positive benefit. Stationary car sharing is less affected by these challenges but is also far less flexible for users. Many free-floating car-sharing services have been taken off the market because of profitability challenges, not only because of the lack of economies of scale.

Even Daimler and BMW, which combined their Car2Go and DriveNow services into ShareNow, have withdrawn from major cities and countries (e.g. Florence, London, Milan, Brussels and North America). Free-floating car sharing will likely continue to be part of multi-modal mobility solutions in the future, but there will be no or only very few additional cities added to the portfolio in the short term due to the challenges around profitability. Free-floating car sharing will not be a disruptive force to inner-city mobility. It will be a niche play, if it can be operated profitably.

The outlook

Stationary car sharing will continue to complement multi-modal mobility. With the current trend towards flexible work arrangements, suburban areas regain attractiveness. Stationary car-sharing services may add further value for those areas. Peer-to-peer offers have grown through the pandemic as people continue to avoid public transport. Retail locations, or car dealers, may find a niche to offer such services. Rental companies could also enter the market with shorter-term, more flexible arrangements.

Peer-to-peer ride hailing will continue to operate successfully in a niche. Professional-service ride hailing (e.g. Uber, Lyft) will continue to face profitability challenges. Ride hailing in its current form adds price pressure on the backs of drivers that are often self-employed.

In the medium term, professional-service ride hailing could benefit from autonomous driving Level 4, as this will replace the driver. Within the next five to 10 years, it may be suitable for very specific high-utilisation cases as the technology is very expensive. It will not be used in mixed-traffic situations any time soon, due to safety and liability concerns. An example could be autonomous ride hailing to bring people from a Park’n’Ride area to an out-of-city access point for existing public-transport infrastructure. Cities that rely on a highly-utilised public-transport infrastructure will not allow Waymo and other operators to take up and load off passengers at inner-city access and switchover points for public transport. The reason is that cities need to scale and increase utilisation of public transport and to manage car traffic.

- Free-floating car sharing, where cars park on public roads within a geo-fenced area. This service exists almost exclusively in larger cities. Smaller cities (<500,000 inhabitants) do not attract free-floating car-sharing services due to expected low utilisation rates. Pre-booking is not possible;

- Stationary car sharing, where drivers pick up cars and return them to dedicated locations. Pre-booking is usually required. Peer-to-peer car sharing (e.g. via Zipcar or Turo) falls under this category as well; and

- Ride hailing. This can be peer-to-peer based or professional-service ride-hailing (e.g. Uber or Lyft). The difference to the traditional taxi ride is that it is fully online-enabled and cheaper. Depending on the supplier and business model, pre-booking is possible. In peer-to-peer-based business models (e.g. Blablacar), pre-booking is usually required.

- Low utilisation rates – particularly problematic in free-floating car sharing as more cars are required than in a stationary setup to allow for flexible access. Drivers use free-floating car sharing for shorter trips, which brings utilisation down;

- High costs for parking – particularly challenging in free-floating car sharing, as these cars park on public roads or in publicly-accessible parking garages;

- High costs related to mistreatments, service and cleaning. Higher-frequency driver changes add to the challenge. Cars need to be regularly cleaned, often daily or on an ad hoc basis;

- Additional costs for relocating cars. Cars need to be regularly re-distributed within the network as clusters form, e.g. at airports in the morning. This requires a human being to pick cars up from remote locations and put them back into those areas that would attract most drivers to the car. This is a daily logistical challenge for free-floating car sharing but affects stationary car sharing as well;

- Cars depreciate more and faster in a shared-driver setup. Remarketing results are substantially lower and refurbishment costs are higher;

- Competing micromobility solutions, such as e-scooters and shared bikes, represent another challenge to the profitability of car-sharing services. Renting a Smart in Frankfurt or an e-scooter costs approximately the same: around €0.20 per minute;

- Car sharing is challenged in two more important use cases: safety regarding transport of (small) children and in terms of cost when running multi-stop trips; and

- Bigger cities have no particular interest in offering preferential conditions for car sharing as they learn that this service does not help manage city car parking.

Ride hailing increases congestion

Ride-hailing businesses are struggling with profitability. There are concerns about the sustainability of the business model as long as cars need a driver. A scientific study from 2019, which analyses the role of ride-hailing companies on traffic congestion in San Francisco, concluded that ride hailing increases congestion. There is some substitution between ride hailing and other road trips, but most road trips add new cars to the road. Ride-hailing vehicles stopping at the curb to pick up or drop off passengers have a notable disruptive effect on traffic flow, especially on major arterials. This was evident at the CES in Las Vegas in 2019: the city lacks a solid public-transport infrastructure and if you choose to take an Uber or Lyft, signs direct you to pick-up and drop-off areas at the major resorts. Downtown, no curb pick-ups and drop-offs are permitted.

Unmet promise

Car sharing has failed to deliver against the promise of contributing to lowering the traffic problems in big cities. It does not reduce the number of vehicles. It takes up parking space. It cannibalises public transport and cities will not give preferential treatment to these services unless they see a positive benefit. Stationary car sharing is less affected by these challenges but is also far less flexible for users. Many free-floating car-sharing services have been taken off the market because of profitability challenges, not only because of the lack of economies of scale.

Even Daimler and BMW, which combined their Car2Go and DriveNow services into ShareNow, have withdrawn from major cities and countries (e.g. Florence, London, Milan, Brussels and North America). Free-floating car sharing will likely continue to be part of multi-modal mobility solutions in the future, but there will be no or only very few additional cities added to the portfolio in the short term due to the challenges around profitability. Free-floating car sharing will not be a disruptive force to inner-city mobility. It will be a niche play, if it can be operated profitably.

The outlook

Stationary car sharing will continue to complement multi-modal mobility. With the current trend towards flexible work arrangements, suburban areas regain attractiveness. Stationary car-sharing services may add further value for those areas. Peer-to-peer offers have grown through the pandemic as people continue to avoid public transport. Retail locations, or car dealers, may find a niche to offer such services. Rental companies could also enter the market with shorter-term, more flexible arrangements.

Peer-to-peer ride hailing will continue to operate successfully in a niche. Professional-service ride hailing (e.g. Uber, Lyft) will continue to face profitability challenges. Ride hailing in its current form adds price pressure on the backs of drivers that are often self-employed.

In the medium term, professional-service ride hailing could benefit from autonomous driving Level 4, as this will replace the driver. Within the next five to 10 years, it may be suitable for very specific high-utilisation cases as the technology is very expensive. It will not be used in mixed-traffic situations any time soon, due to safety and liability concerns. An example could be autonomous ride hailing to bring people from a Park’n’Ride area to an out-of-city access point for existing public-transport infrastructure. Cities that rely on a highly-utilised public-transport infrastructure will not allow Waymo and other operators to take up and load off passengers at inner-city access and switchover points for public transport. The reason is that cities need to scale and increase utilisation of public transport and to manage car traffic.

Ride hailing increases congestion

Ride-hailing businesses are struggling with profitability. There are concerns about the sustainability of the business model as long as cars need a driver. A scientific study from 2019, which analyses the role of ride-hailing companies on traffic congestion in San Francisco, concluded that ride hailing increases congestion. There is some substitution between ride hailing and other road trips, but most road trips add new cars to the road. Ride-hailing vehicles stopping at the curb to pick up or drop off passengers have a notable disruptive effect on traffic flow, especially on major arterials. This was evident at the CES in Las Vegas in 2019: the city lacks a solid public-transport infrastructure and if you choose to take an Uber or Lyft, signs direct you to pick-up and drop-off areas at the major resorts. Downtown, no curb pick-ups and drop-offs are permitted.

Unmet promise

Car sharing has failed to deliver against the promise of contributing to lowering the traffic problems in big cities. It does not reduce the number of vehicles. It takes up parking space. It cannibalises public transport and cities will not give preferential treatment to these services unless they see a positive benefit. Stationary car sharing is less affected by these challenges but is also far less flexible for users. Many free-floating car-sharing services have been taken off the market because of profitability challenges, not only because of the lack of economies of scale.

Even Daimler and BMW, which combined their Car2Go and DriveNow services into ShareNow, have withdrawn from major cities and countries (e.g. Florence, London, Milan, Brussels and North America). Free-floating car sharing will likely continue to be part of multi-modal mobility solutions in the future, but there will be no or only very few additional cities added to the portfolio in the short term due to the challenges around profitability. Free-floating car sharing will not be a disruptive force to inner-city mobility. It will be a niche play, if it can be operated profitably.

The outlook

Stationary car sharing will continue to complement multi-modal mobility. With the current trend towards flexible work arrangements, suburban areas regain attractiveness. Stationary car-sharing services may add further value for those areas. Peer-to-peer offers have grown through the pandemic as people continue to avoid public transport. Retail locations, or car dealers, may find a niche to offer such services. Rental companies could also enter the market with shorter-term, more flexible arrangements.

Peer-to-peer ride hailing will continue to operate successfully in a niche. Professional-service ride hailing (e.g. Uber, Lyft) will continue to face profitability challenges. Ride hailing in its current form adds price pressure on the backs of drivers that are often self-employed.

In the medium term, professional-service ride hailing could benefit from autonomous driving Level 4, as this will replace the driver. Within the next five to 10 years, it may be suitable for very specific high-utilisation cases as the technology is very expensive. It will not be used in mixed-traffic situations any time soon, due to safety and liability concerns. An example could be autonomous ride hailing to bring people from a Park’n’Ride area to an out-of-city access point for existing public-transport infrastructure. Cities that rely on a highly-utilised public-transport infrastructure will not allow Waymo and other operators to take up and load off passengers at inner-city access and switchover points for public transport. The reason is that cities need to scale and increase utilisation of public transport and to manage car traffic.