Ambitious EU battery regulations pose automotive challenges

02 May 2023

Batteries for electric vehicles (EVs) will need to be more sustainable. Planned legislative changes directly impacting the automotive industry in Europe will soon come into play. Upcoming EU regulations will overhaul existing battery rules to make the components more economically circular and increase transparency in the sector.

These measures will impact the whole lifecycle of an EV battery, including the sourcing and recycling of materials. The move could have global ramifications as Europe is intent on taking on a leading role within the battery industry by improving social and environmental standards along the supply chain.

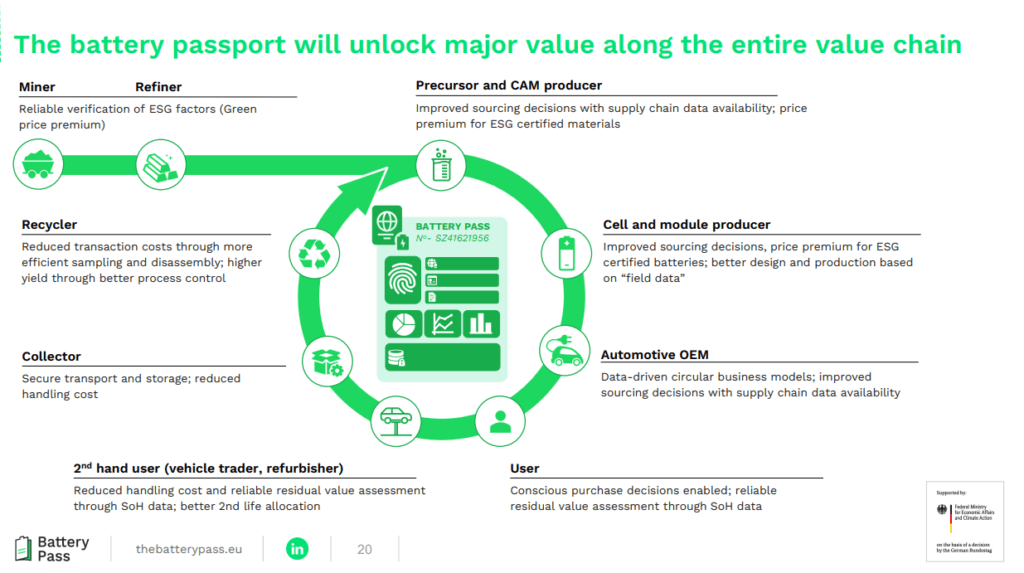

Crucially, it will also introduce a battery passport across the EU by 2027. This will be the first digital product passport implemented in the bloc.

‘The directive is a game-changer since for the first time a regulation focuses on the entire lifecycle of a product and will enable transparency,’ Stephanie Schenk, project lead at the Battery Pass consortium and project manager at system change company, Systemiq, told Autovista24.

‘It comes along with significant value potential and will enable beneficial business models. It is therefore not only a compliance tool but also offers lots of opportunities.’

Seen as an important step to reaching climate neutrality on the continent, the new rules aim to make the European battery industry more competitive. But they also pose challenges, not least for automotive manufacturers. A closer look at the planned regulations reveals why.

Sustainability requirements

The main takeaway is that the new law, which will be introduced gradually from 2023, will enforce certain sustainability requirements for batteries. These EV components will have to come with a label describing their entire carbon footprints, from mining to production and recycling.

Additionally, manufacturers will have to disclose the environmental impact of battery materials. A year and a half after the regulation comes into force, only EV batteries with an established carbon footprint declaration, will be allowed on the market.

Since batteries contain valuable materials, the EU wants to ensure that no unit is lost to waste, especially as their numbers are set to grow exponentially. After all, demand for batteries is rising rapidly and is expected to increase 14-fold by 2030. Consulting firm McKinsey projects that the lithium-ion battery chain could grow by 30% annually from 2022 to 2030.

To lessen the environmental impact of sourcing raw materials, EU legislators want to increase the recycled content of batteries. This will help retain critical battery raw materials, with the bloc setting up minimum quotas for lead, cobalt, lithium, and nickel.

Targeted lithium recovery rates, for instance, have been set at 50% by 2027 and 80% by 2031. Manufacturers will also have to recover 90% of nickel and cobalt, with this figure rising to 95% in 2031. The goal is for all EV batteries to be collected for reuse in a second life or for recycling.

Battery passport

The EU battery regulation, which will replace an outdated directive from 2006, has been welcomed by green NGOs. Transport and Environment (T&E) said companies will now have to comply with rules to prevent environmental, human rights and labour abuses in supply chains.

The EU reaffirmed that by setting battery-sustainability standards, it will promote the transition to green technologies and responsible sourcing globally. A key component of the upcoming rules is the introduction of a digital battery passport. This will bundle together important lifecycle data.

The Battery Pass consortium includes manufacturers such as BMW and Audi and is co-funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate. It said the passport will back circular management by providing a digital infrastructure to document business and sustainability data. This will include the carbon footprint of the EV battery, supply chain due diligence, resource efficiency, durability, as well as battery materials.

Challenges and opportunities

For manufacturers, this means having to make a lot of data public, including the health and performance of the battery. The measures will make it easier to calculate the value of a used EV battery. This is good news for consumers who will benefit from useful information about the state of the battery.

But companies along the value chain will need to report more sensitive data too, which they might not want competitors to see, especially when it comes to an EV battery’s composition. ‘That is to some extent of course, still the secret sauce of an organisation,’ explained Schenk.

‘Since the industry has certain concerns about this issue, further discussions can be expected in the coming months, also in the context of an upcoming delegated act of the regulation focusing on specifying the access rights for the battery passport. However, most of the requirements do not go too deeply into sensitive areas,’ she added.

The Battery Pass consortium is developing guidance on all aspects of the passport, with a special focus on how sustainability objectives can feasibly be implemented across the industry. The German-funded group is taking an international approach towards this end.

Schenk said that the required reporting set out by the upcoming battery regulations should ideally be low-cost and not a significant burden on companies. She also highlighted that the system should be based on certain principles with interoperability at the core, ideally on a global level.

‘The US has just started looking into something similar to the battery passport. Because Europe currently has front-runner status, the US will hopefully be looking at what we do when we try to exchange and share best practices,’ she said.

A key challenge for automotive companies will be the actual implementation of the battery passport by 2027.

‘The timeline is ambitious if you look at what needs to be set up in terms of technology to make the reporting and data sharing possible. Here we need a lot of collaboration and interaction with other initiatives such as the Global Battery Alliance, as well as globally with the US and Asia,’ Schenk explained.

The automotive industry does have time to take the necessary steps to make the upcoming changes. As such, the battery passport can offer additional opportunities, especially if it is used as a business tool instead of a mere cog of compliance.

Will the regulation transform EV batteries into totally green components? It is highly unlikely, but as Schenk points out, the potential for circularity via the reuse and feeding of raw materials back into the production cycle will make a significant difference.

‘It will help create an era of circularity that has a massive advantage compared to internal-combustion engines because fossil fuels are a finite resource and cannot be recycled or re-used. In terms of sustainability and circularity, this is a huge opportunity. The battery passport will also create a level playing field so that you can more easily compare organisations in the future,’ Schenk said.