How Norway and pop band A-ha paved the way for electric-car adoption

01 November 2021

In a three-part series, José Pontes, data director at EV-volumes.com, considers the evolution of the electrically-chargeable vehicle (EV). In part one, he focuses on Norway – one of electrification’s first movers and an indicator of what could lie ahead.

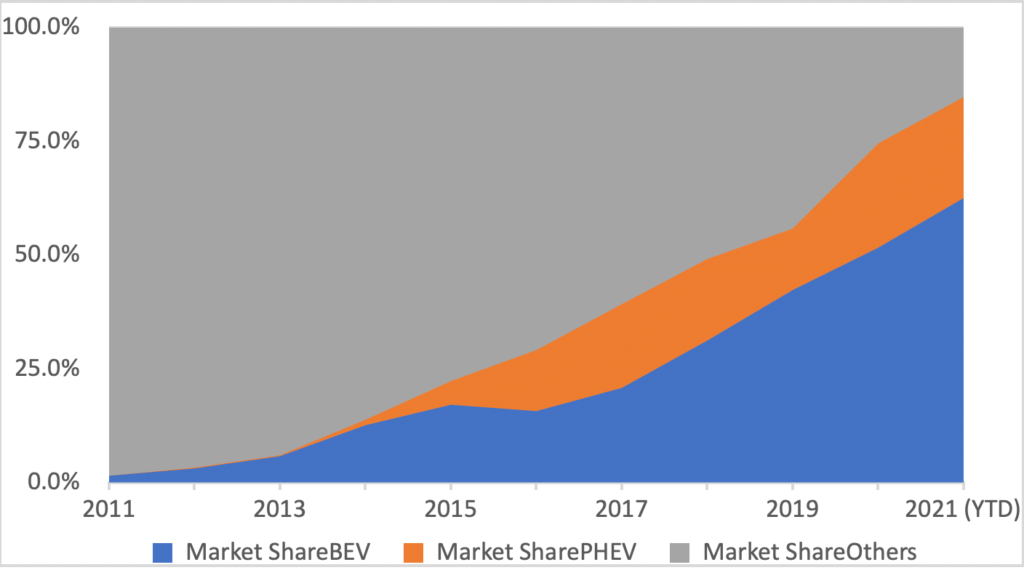

To know more about the social and economic consequences of transport electrification, look no further than Norway. With currently-unbeatable market shares (62.5% battery-electric vehicles (BEVs), 22.2% plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), 15.3% others) this year, the country works as a preview of the future for other regions.

Since the third age of the EV started a decade ago, Norway was the first market to reach the 1% market share in new registrations of the technology in 2011. It was the first market to reach one in every 100 passenger vehicles being an EV (2014), and the first to achieve double digits, both in market share (2014) and fleet (2020).

As such, it is clear that Norway will be the first country in the world to complete the electrification process, with the added advantage of 98% of all electricity in the country coming from renewable sources, in particular hydropower.

Norway’s vehicle market breakdown

Norway is a pioneer in road-transport electrification, being the country with the most advanced process. EVs currently represent 85% of all passenger-car sales, with BEVs alone representing 63% of all registrations.

Interestingly, the PHEV market share has been relatively stable since 2016. Meanwhile BEVs, after one year of stagnation in 2016, have resumed their previous steady, but certain, growth rate. This is only possible because of the stability of purchase incentives in Norway.

Expect Norway’s EV share to represent close to 100% of the overall automotive market by 2023, with BEVs having more than 95% of the market by 2024. This pre-empts the country’s 2025 zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) targets.

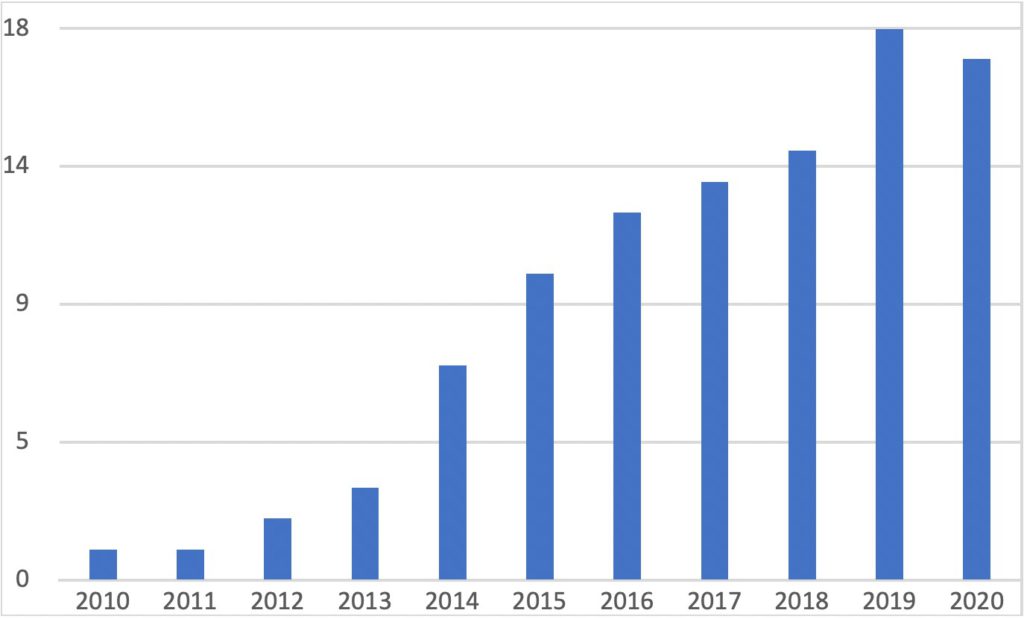

Vehicle growth rates in Norway

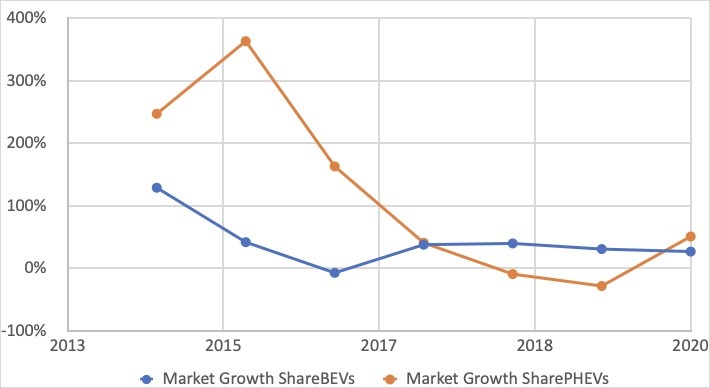

As shown in this graph documenting the growth rates of both powertrains, PHEVs experienced steep growth from 2014 until 2016, thanks to increased incentives in the second half of 2013. After that, the technology has either followed that of BEVs (2017 and 2020) or has seen declining sales (2018 and 2019).

BEVs, due to stable incentives, have experienced steady growth, following the classic smooth down-slope growth rate of maturing markets.

Total fleet percentages

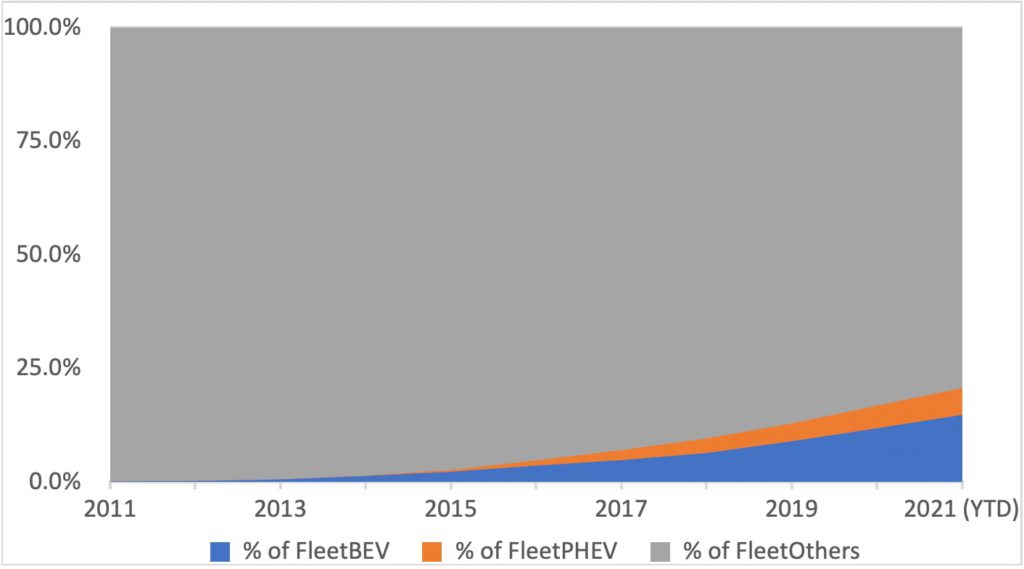

Effects on the overall passenger-car fleet

When it comes to new registrations, the electrification process is almost complete. Replacing the total fleet of passenger cars will take a few more years, the graph above shows. While the plug-in share in new registrations is already at 85%, the same rate in the total fleet of passenger cars is still at 21%.

Despite this, the effects of overall fossil-fuel consumption in the country are already visible, as Norway has seen falling fuel sales since 2017, at a 3-5% yearly rate.

It is worth noting that an effect of the dwindling sales of fossil fuels is partly because some petrol stations are already replacing their fuelling points with fast-charging stations.

Level of BEV incentives

How big are the incentives?

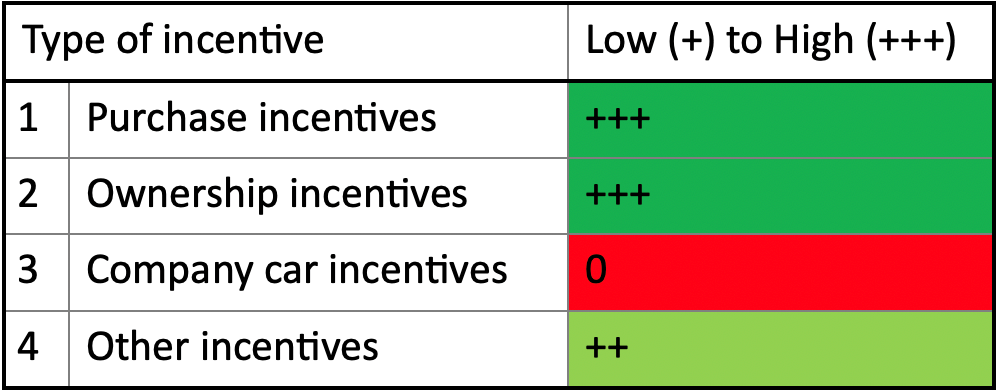

Incentives in Norway are considerable. While company cars do not have special perks or incentives, BEVs have several significant incentives, not only at point of purchase, like the exemption of the 25% VAT or registration taxes but also during the life of the car.

These benefits include reduced road tax, bus-lane use, free tolls, ferries, and parking. However, these last three were changed in 2018, when local authorities were granted the right to change the free use of these services.

Some of these are of particular significance in some areas of Norway, like Bergen, where free ferries can mean a big saving each month. Crossing the fjords by ferry can be expensive, so it is no surprise that in areas such as Bergen this incentive is being mentioned as the number one reason to buy an EV. On top of this, there are also some indirect incentives, like special licence plates, or subsidies for home chargers. PHEVs, while less significant, also have perks, namely significant tax reductions.

Zero emissions

Another important driver for change is the zero-emission mandate, set to start in 2025, when all new-passenger cars, urban buses and LCV registrations should be for zero-emissions vehicles (ZEVs). The mandate is also set to be enforced for long-distance buses and heavy-duty trucks in 2030, although the requirement only mandates a 75% ZEV quota for the former and a 50% quota for the latter.

Currently, there are discussions to change incentives in the 2022 Norwegian state budget, namely:

- The reduction in yearly traffic tax could be removed

- PHEV incentives to be significantly reduced, and the minimum electric range to increase from 50 km to 100 km (WLTP)

- An increase in CO2 tax.

Benefits and incentives include purchase-tax exemption, purchase incentive, VAT, import-tax and ownership-tax exemption, bus-lane use, toll exemptions, free parking and free ferries. They can also include benefit-in-kind tax exemption, charging-cost deductibility, special licence plates and EV-charger subsidies.

BEVs per charging point

The charging-anxiety ratio

EVs do not mean much without a reliable charging infrastructure (CI). For BEV success, three variables should be met:

- Price should be close to ICE models

- Range should be enough for the needs of the buying public, thus avoiding range anxiety

- There should be enough CI to avoid charging anxiety, something that can be as damaging for EV adoption as range anxiety.

CI maintenance also needs to be considered. The official numbers assume that all charging stations are operational, which is not realistic, so the frequency of downtime should also be taken into account.

The same logic applies to the EV driver. When preparing a road trip drivers will need to have a plan B (or even plan C) in case the initial charging station is offline.

Due to faster growth rates in BEV sales, the number of vehicles per charging point has grown significantly over the years, from two BEVs per charging point in 2012, to 18 in 2019. This growth has led to queues at some charging stations. Fortunately, since then the CI development has increased significantly, stabilising this important ratio.

EV ownership goes mainstream

The demographics of BEV ownership have been changing, becoming less distinctive from the overall market, as the EV sector matures and merges into the mainstream. A 2016 survey by Transportokonomist Institutt (TOI), an Oslo-based research centre into EV ownership, showed that families with BEVs were on average younger (47 years vs 56 for ICE), higher educated, travelled longer distances for work (25km vs 18km), and owned more vehicles per capita. The same survey in 2018 revealed the average age of EV ownership (51 years) came closer to the main market, with the same happening in the remaining indicators.

Additional studies showed that 59% of BEV owners charge at home, with this percentage growing to 74% in the case of PHEV owners.

Interestingly, the main reasons presented for buying a BEV or PHEV are different. Peer-to-peer influences were identified as the main driver for BEV purchases. While on the PHEV side, dealerships and advertising are mentioned as the main reasons for purchase.

A-ha and a Fiat Panda

At first sight, the cold climate of Norway would not appear the best place to start the EV revolution, but some factors did align. One of them had to do with the Norwegian pop band a-ha and a Fiat Panda.

In 1989, two of the band members brought a privately converted Fiat Panda to Norway. While driving it through Oslo, they refused to pay road tolls and subsequent fines, in protest against the lack of incentives for EVs.

The little Panda was confiscated more than once, but when being auctioned to pay for the fines, no one else would buy the car, so the two band members bought it back again for a symbolic price.

This happened more than once and these bizarre events gained media attention, fuelling the popularity of the EV cause, and ultimately originating the start of EV incentives in 1990, with the exemption of the import tax.

From then on, the EV movement started to gain some traction, and further incentives were introduced throughout the 1990s. This kickstarted a local startup company, Pivco, to develop and introduce the small PIV3 model in 1995. The small Norwegian company made 120 units, which motivated it to create a new, more capable model, which they called PIV4.

Nevertheless, without enough revenue to finance its development, once the new model was ready in 1999, the company was in serious financial trouble. Ford acquired the business and transformed the PIV4 into the Think City, with the small city EV production starting in 2001.

After only a year, in 2002, with 1,005 units being produced, the changing winds in US politics drove the project to a halt. Units sold in the US and UK were re-exported to Norway, the only place where EVs still had demand by the mid-2000s.

Once again, Norwegian entrepreneurs took the initiative to resurrect the little EV, and as such, in November 2007, a new and improved Think City resumed production, selling 100 units in little less than a year.

In 2011, Norway profited from these past efforts and incentives to become one of the focus markets for the introduction of a new generation of EVs, like the Nissan Leaf and Mitsubishi I-Miev.

It was then that the EV market started to develop more significantly. While the incentives and charging infrastructure were already in place, there was a lack of appealing models prior to this. Sales grew from the previous couple of hundred vehicles per year, to over 2,000 units in 2011. Volumes surpassed the 1% market share threshold, at a time when most other markets still only had symbolic sales.

Keep an eye on Autovista24.com for the second instalment of Pontes’ three-part special. Subscribe to the daily Autovista24 email to get all the latest automotive analysis straight to your inbox.