UK car market Europe’s pioneer for electric-car adoption

16 March 2022

José Pontes, data director at EV-volumes.com, examines the UK, one of the biggest electric-vehicle (EV) markets in Europe.

Although not Europe’s biggest electric-car market, the UK comes second behind Germany and is ahead of France, making it one of the most important markets to watch in the region. In 2009, the government began early electric-car trials in London, when then local mayor Boris Johnson announced plans to deliver 25,000 charging spots by 2015. The aim was to have 100,000 EVs on the road by then.

But the adoption of electric cars in the UK was slower than expected. In 2015, there were only 8,000 EVs in the Greater London area, or only 8% of the goal set by Johnson six years earlier. However, the UK was one of Europe’s early pioneers of electromobility. In 2014 it was the leader in fast-charging infrastructure, had local manufacturing of the best-selling electric vehicle (EV) Nissan Leaf. Buyers also had significant incentives, like the plug-in car grant (PICG), which started in 2011. It provided a subsidy up to £5,000 (€6,000) per vehicle, or an exemption from the London congestion charge.

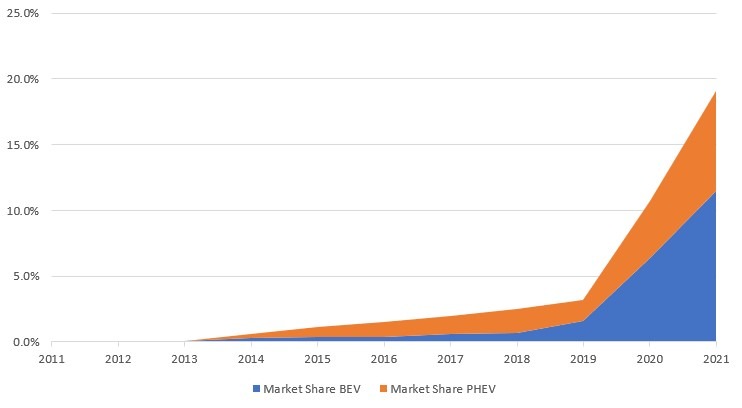

Market share of BEVs and PHEVs: 2011-2021

The UK electric-car market share went through three stages: from basically non-existent up to 2014, steady growth until 2019, to the recent surge in the last couple of years.

With the EV category already representing close to 20% of the 2021 overall automotive market, up from just 3% in 2019, it looks like EVs are now in the steepest part of the S-curve. The coming years look set to see historical changes in the automotive market, with an EV share of over 80% by 2030. This percentage is expected to reach over 95% by 2033, by which time the electrification process of the automotive passenger car market in the UK will be done.

UK market growth rates

Electric-car growth rates

Up until 2016, plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) were growing significantly faster than pure electric cars. Changes came in with the PICG in April 2016, with the maximum grant reduced to £4,500, a price cap of £60,000, and PHEVs being granted PICG according to their emissions.

As a result, sales were more balanced, with steady growth rates from both battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) and PHEVs. But with further subsidy cuts in 2018 (maximum £3,500 PICG and exclusion of most PHEVs), PHEVs came down in 2019, by 15%. Meanwhile, BEVs surged, more than doubling the results of the previous year.

In 2020, despite no longer having access to the PICG, PHEVs returned to growth, while pure electric cars continued to flourish, jumping 183% from the previous year, despite a reduction of the PICG to £3,000 in March 2020. A new PICG cut was made in March 2021, to just £2,500 and a price cap of £35,000.

2021 witnessed both technologies continuing to grow at an accelerated pace, and despite another PICG reduction set to start this April to a maximum amount of £1,500 and with a price cap of £32,000, the EV market is expected to continue growing significantly. Even if the PICG is removed all together, possibly in 2023, there will still be massive benefit-in-kind advantages for company-car drivers to continue pulling the market up. And those cars are also the ones giving the UC market a headache as the supply of used cars is pushed by the benefit in kind (BiK) tax, but there is still very low used-car demand.

Still pioneering electric-car adoption

The UK EV market is expected to be one of the first European markets to remove purchase subsidies to sustain its electrification process. Such a move would confirm its pioneering role among the principal European automotive markets.

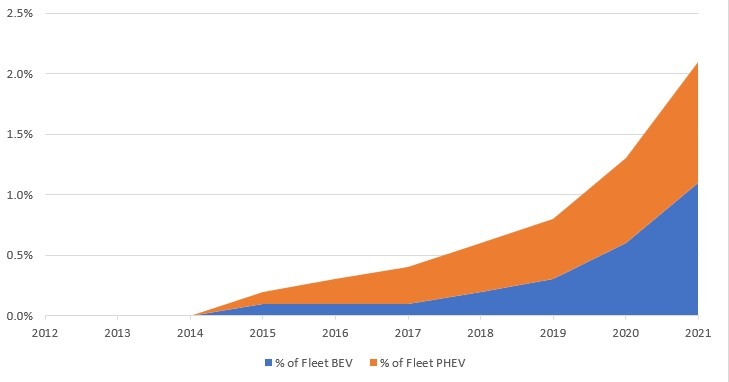

Effects on the overall passenger car fleet (% of fleet)

When it comes to fleet numbers, the needle only started to move by the end of 2015, followed by slow but steady growth through to the end of 2019. The following two years saw a significant rise in the vehicle replacement rate, with the EV share jumping to over 2% in just two years.

Still, with the current EV fleet representing less than 2.5% of total numbers, and the UK’s internal-combustion engine (ICE) ban set to be enforced by 2035, expect a steep increase in the ICE replacement rate around that time, with a complete phase-out by 2050.

How big are the incentives?

| Level of BEV Incentives | ||

| Type of incentive | Low (+) to High (+++) | |

| 1 | Purchase incentives | + |

| 2 | Ownership incentives | ++ |

| 3 | Company car incentives | ++ |

| 4 | Other incentives | ++ |

There is a purchase incentive of up to £1,500 for BEV passenger cars below £32,000, including VAT and delivery fees. Other vehicle categories, like motorbikes, vans, lorries and buses, have their own purchase incentives. The current terms are valid until 2023.

In the UK, there is no road tax (RT) for BEVs until 2025, and they are exempt in the clean-air zones (CAZ) during the same period, including London. Having said that, introduction of a national road pricing scheme, though controversial, could be introduced in the short to medium term to compensate for the forecasted loss of road-tax revenue as the downward trend of reduced ICE new-car sales will only gather pace as the proposed 2030 ban of new ICE vehicles approaches.

Reduced BiK taxes for BEV company cars stand at 2%, when the rates for regular ICE models can go up to 37%, according to their emissions. These rates are set to stay at this threshold at least until 2024. There is, however, a concern for the fleet and business sector, that a sudden hike in BiK rates from 2025/2026 by the UK Government (to gain more tax revenues) could kill the current momentum of the phasing out of petrol and diesel cars from their fleets.

Low tax rates and the security of a five-year roadmap on future charges have seen the BiK regime become the single biggest driver of zero-emission vehicle uptake in the UK. It has driven a surge in decarbonisation within the company-car and salary-sacrifice markets, where BEVs already make up 8% and 22% of the total fleet, respectively.

Clean air zones

Between RT exemption, linked to CAZ exemption, and BiK reduced rates, the first is less effective for new EV adoption, but would play an important role in used EV adoption, especially if it were made through a stable roadmap. For instance, RT and CAZ exemption during the first 10 years of an EV on the road.

Besides special licence plates, businesses, charities, the public sector can get grants up to £350 per socket for installing up to 40 charging points for their employees and car fleets. People working from home can apply to the workplace charging scheme, if their home address is listed as a place of business.

In addition, the UK has just enacted legislation that requires the provision of cabling and switchboard capacity for EV charging in all new and substantially renovated buildings.

Finally, the UK government set a target to have all its fleet of cars and vans to be 100% zero emission in 2027 and banned the sale of new regular petrol and diesel vehicles in 2030. A mandate is set to start in 2035, when all new vehicles registered must be based on zero emissions.

Over the past few years, the UK government has gradually introduced CAZs in major cities, starting with London in 2019, with the clear aim of eliminating older high-emission petrol and diesel vehicles from the UK.

The scheme has been rolled out to several other UK cities. Ultra-low emission vehicles, especially BEVs, have a clear benefit, as the daily charge to enter CAZ cities looks set to increase over time for non-compliant vehicles. For high mileage drivers, whether they are private or fleet drivers, this makes a compelling case to switch to fully compliant vehicles like BEVs.

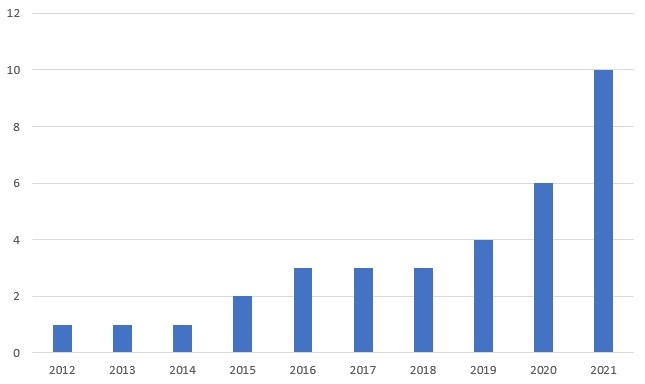

BEVs per charging point

In all markets, EVs do not mean much without a functioning charging infrastructure, and this framework needs to be properly maintained to ensure car charging points are kept operational. For BEV success, three variables should be met:

1) Price should be close to internal-combustion engine models;

2) Range should be enough for the needs of the buying public, thus avoiding range anxiety;

3) Drivers should have enough CI to be able to charge while on the road, avoiding charging anxiety, something that can be as damaging for EV adoption as concerns about range.

Due to an early focus on CI development, the ratio of BEVs per charging point stayed stable during most of the electrification process, with this number ranging between one, in 2012, to three, in 2018. The recent registration surge without a corresponding quick increase in CI, has led to an increase of the EVs to charging points ratio. While 10 BEVs per charging point in UK is still far from the ratio of 17 in Norway, it is worlds apart from the two BEVs per charging point that the Netherlands has, highlighting the need for a swifter deployment of charging infrastructure.

The UK shows that fiscal incentives can be a significant factor in EV adoption. It will be interesting to see how the market will behave, when the purchase incentive is removed. Expanded road tax and CAZ tax exemptions could be a driver for EV adoption in the used car markets, especially CAZs, as they expand throughout the main urban areas of the UK.

The initial investment in CI has also allowed it not to be a limiting factor in the EV uptake up until now.

Used EVs are a key to long-term success, because otherwise the new vehicles will not find a second-hand market, hurting their leasing and resale values, thus delaying the market transformation.

Finally, one of the biggest questions for the future is how fast the used-car market for BEVs develops and when the increased supply of used BEVs in the coming years meets an according demand. Besides the forementioned benefits or restrictions, the current developments around energy costs can play a major role in establishing the not-yet found balance between the BEV new-car and used-car market.