Energy costs and skill shortages hampering UK’s automotive industry

30 June 2022

Attending the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) latest event, Autovista24 editor Phil Curry took stock of the UK’s automotive industry.

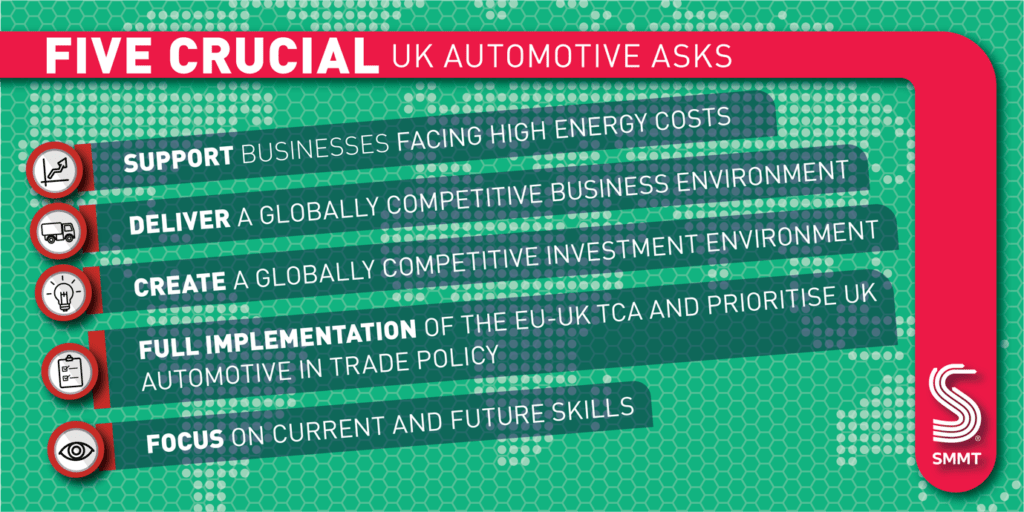

The UK’s automotive industry is facing numerous challenges this year. As energy costs are spiralling, jobs are at risk and Brexit concerns remain. These issues are putting British manufacturers at a disadvantage to those based in the EU, according to the SMMT.

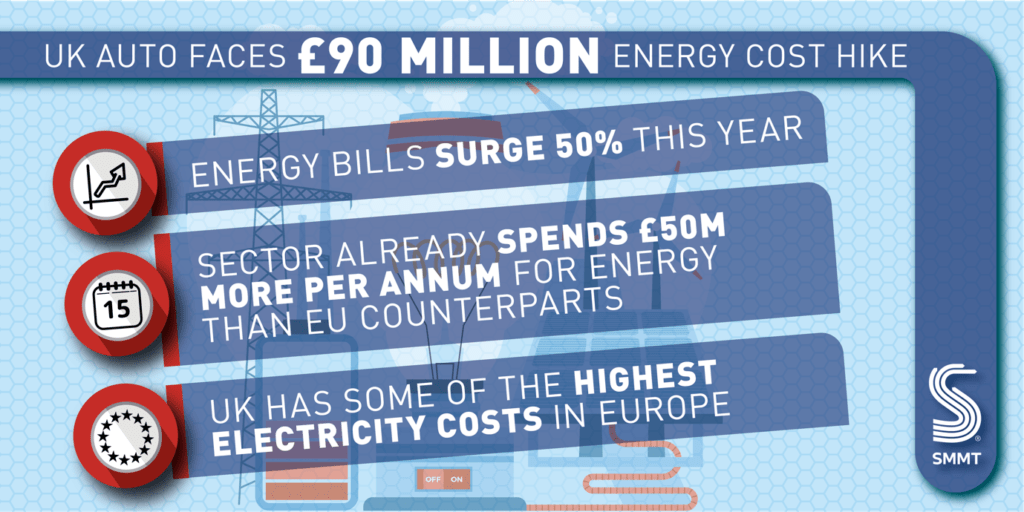

A new report: From full throttle to full charge, unveiled at the SMMT International Automotive Summit in London, highlights the risks the sector must overcome, giving a stark snapshot of the problems ahead. This year alone, UK vehicle manufacturers and suppliers face a combined £90 million (€104.5 million) increase in energy bills, equivalent to more than 2,500 jobs.

At the same time, the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union is still causing problems for the industry. A 2024 deadline for ‘rules of origin’ regulations set out in the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) is looming. In just 18 months companies based in Britain will be required to have at least 45% of vehicle components sourced from the UK or EU.

There are also concerns around the workforce, with upskilling and retraining required in the shift to electrification. Plus, there is the need to bring new people into the industry to create a more diverse automotive culture.

‘From COVID-19 impacts to component shortages, supply-chain disruption to trade uncertainty, and regulatory change to rising inflation, the challenges facing this sector are immense,’ SMMT chief executive Mike Hawes commented.

‘Nevertheless, addressing the UK’s high energy costs is the industry’s number one ask. Help with this now will help keep us competitive and be a windfall for the sector, stimulating investment in innovation, R&D, training – all reinvested in the UK economy. With the right backing, this sector can drive the transition to net zero, supporting jobs and growth across the UK and exports across the globe,’ he added

Energy prices not competitive

Energy costs in the UK have surged by 50% in recent months, the most expensive of any European automotive manufacturing country. They are around 59% higher than the EU average, meaning carmakers in Britain could have saved almost £50 million on energy costs if they were buying power from the continent instead.

The additional cost of producing vehicles and components in the UK is putting manufacturers at a competitive disadvantage, the SMMT’s report states. This is affecting the build up of momentum in the industry and impacting interest in investment opportunities, crucial when a large transformation to electrification is underway. However, there is a desire to invest in the country’s automotive industry, evidenced by £4.9 billion publicly committed to UK vehicle production in 2021 following the signing of the EU-UK TCA.

Energy is typically the second-largest in-house cost to manufacturing, so price increases do hit the sector hard. As the automotive industry looks to shift away from gas and fossil fuels, with power generation coming from more renewable sources likes hydrogen, biomass, higher costs could undermine this transition.

The sector also faces supply chain problems which are increasing lead times. Vehicles are typically sold in advance at a fixed price. These supply times, combined with energy-price instability, erodes already low margins as a result.

Electric vehicles (EVs), and notably their batteries, are more energy intensive to produce than fossil-fuel cars. This means affordable clean energy will be a decisive factor in decision making when it comes to building new models, and that could be outside the UK.

‘The UK automotive industry needs support towards electricity costs by awarding relief equivalent to that of other energy intensive industries, which we are not classed as, while maintaining our climate change agreements,’ stated SMMT director of policy and government affairs, Konstanze Sharring. ‘This includes delivering low cost, zero-carbon electricity and a national supply of hydrogen.’

Transitioning the workforce

During COVID-19, apprenticeship levels in the UK’s automotive sector dropped dramatically. At a time when the industry is transitioning to new technologies, such a decline is impactful, leaving many businesses seeking a quick influx of skilled staff.

The advanced manufacturing supply chain has been hardest hit. With a cumulation of factors, including Brexit, COVID-19, and the UK’s ageing workforce, filling semi-skilled roles in the supply chain is challenging., Plus, these gaps have already led to production stoppages and even plant shutdowns. Automotive manufacturers face the dual task of maintaining current production to stay in business and service today’s market, while developing the expertise and engineering infrastructure to create new vehicles and powertrains.

The 2030 ban on the sale of new internal-combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, and the need to ramp up production of batteries and EVs by 2024 to meet Rules of Origin requirements, means the workforce faces short upskilling timeframes.

The SMMT’s report states that the UK possess few qualified workers who can manufacture battery cells and yet, according to Faraday Institution estimates, by 2025 the country will require 5,000 such engineers, increasing to 20,000 in 2030.

‘We need to think about upskilling the current workforce, we cannot leave anyone behind,’ commented Emar Martin-Vignerte, head of political relations and governmental relations at Bosch UK. ‘Firstly, taking the current workforce and then getting them involved the electrified environment. Then we are talking about automated driving, which will bring more digitalisation and software skills which we as an industry do not have yet.’

‘Software has always been in the automotive industry but it has tended to be out in the supply base,’ stated Tim Slatter, chair, Ford of Britain. ‘That kind of leads you to a very distributed electrical architecture which is hard to update with over-the-air technologies. Therefore, we are now seeing a trend towards central and more OEM-developed software, and that is probably the area where it is harder for us, as a vehicle manufacturer, to retrain and rescale our existing people.

‘So, this is where we spend a lot of time in terms of external recruitment, looking at parallel industries where we can recruit people from, but also going into the education system and learning how to recruit software experts from schools or universities. It is essential that we are targeting the same people as some of the big technology companies, because today, everyone is having to deal with software,’ he added.

The issue of electrification is also one that will impact the skills sector, and could lead to job losses, if businesses are not ready. The report states that, some 22,000 jobs, £11 billion of turnover, and £2 billion gross value added (GVA) is reliant on ICE-based technologies.

Elements of the wider automotive supply chain are also ICE focused. For example, 44% of automotive products are identified in basic metals, and 15% in fabricated metals. The SMMT warns that while businesses operating in some of these fields will transition, some may not, and the jobs and skills involved with ICE vehicle may not be transferable to EVs.

‘If you think about the transitions from the current workforce, for the combustion engine, we need around 10 workers to develop and also to manufacture each engine,’ added Martin-Vignerte. ‘When we go electrified engines, we need only one person. So, we need to think about the skills for 2030 onwards and that not only do we have the challenge of the transitions to the different technologies, but also how can we upscale people, and what skills will be required in education schemes.’

Creating automotive competition

The SMMT is also calling for an industrial and regulatory framework, coupled with a clear strategy and delivery plan. This is to ensure the UK is best placed to develop, manufacture, and market electric, hydrogen, and alternatively-fuelled zero-emission vehicles. This must provide manufacturers with access to EU zero-tariff trade from 2024, when the next phase of Rules of Origin comes into force.

‘The government must ensure that Rules of Origin reflect appropriate sourcing of parts and critical raw materials, in particular for batteries and other electric-car components, so that UK-built zero-emission vehicles can be freely exported, without punitive and uncompetitive tariffs,’ the SMMT’s report states.

‘Increasingly stringent Rules of Origin from 2024 onwards enhance the need for attracting the wider electrified supply chain to increase the value chain in favour of UK origin. This will help avoid the risk of future tariffs – especially with exceptionally high prices for critical raw materials such as lithium – as all markets pursue net zero against a backdrop of sustained economic headwinds,’ it continued

There are also headaches over the Brexit process which, despite being finalised through the TCA, is still a discussion point for the UK’s automotive industry.

‘Brexit was a trauma, but it is not yet ‘done’ and the effects of it still being felt,’ stated Hawes. ‘The promised working groups with the EU have not met, critical UK-specific regulation has not been hammered out. Brexit costs are there, and we cannot ‘kaizen’ them out. The progress promised has not materialised.’

One such regulation is type approval. Currently the UK follows the EU type approval regulations, while it establishes its own rules. ‘Any future UK scheme must not impose unnecessary burdens on businesses operating in the UK market and must be introduced with adequate phased in lead times to avoid delays in bringing products to market, which could impact both the viability of the industry and consumer choice,’ the SMMT states. ‘It is imperative that the UK obtains the necessary legal powers to be able to introduce a pragmatic scheme while ensuring that the market continues to conform to the latest relevant safety and environmental standards.’

There is much to be done to ensure the UK remains relevant when it comes to the automotive market in Europe. New technologies require new skills, and investment. Only collaboration with government can ensure a smooth process. But with the introduction of new challenges caused by economic pressures, the next SMMT report in 12-months’ time may paint a different picture of the requirements of the automotive industry.