The Netherlands – where EV charging points grow like tulips

23 November 2021

In part two of a three-part series looking at the evolution of the electrically-chargeable vehicles (EVs), José Pontes, data director at EV-volumes.com, considers the Netherlands and its relationship with the technology.

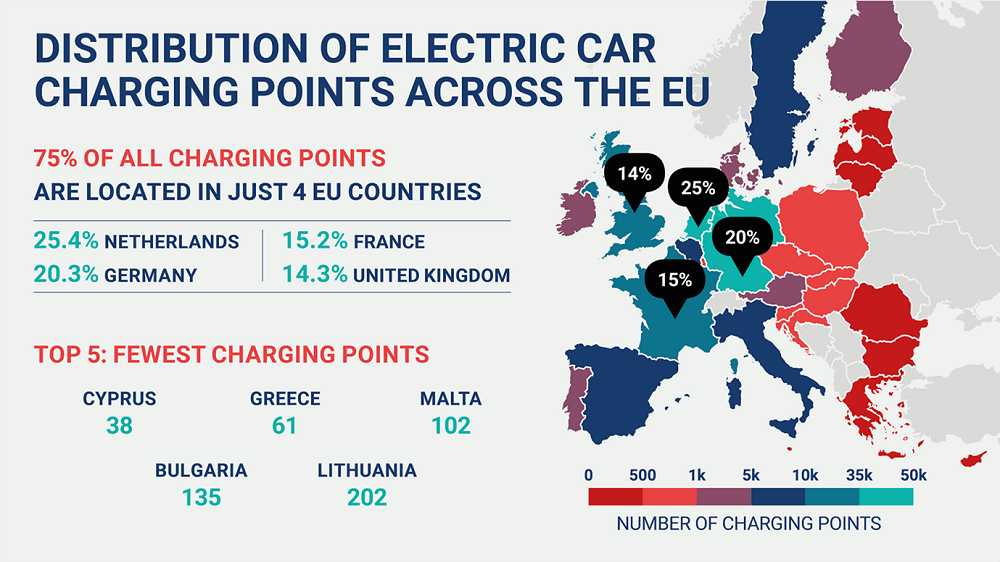

This ACEA EV charging stations map pretty much says it all. Despite being only the 31st largest country in Europe, the Netherlands has the largest number of electric car charging points, around 80,000, on the continent. Its currently unbeatable charging-infrastructure (CI) density works as a preview of the future for other markets.

To know more about the social and economic consequences of electrification, look no further than the Netherlands. It is no coincidence that Tesla decided to open its supercharger network to other brands in this market first.

EV Charging points not keeping pace with demand

Since the third electric age started over a decade ago, the Dutch government has extensively supported EV adoption through fiscal incentives and promoting CI. Consequently, in 2010, when EVs were still in their infancy, there were already 400 electric car charging points in the country, with that number surging to 1,841 in the following year. As a comparison, a large country like Poland is still to hit that number of EV charging stations in 2021, 11 years later.

As such, charging anxiety is almost non-existent. The country is well served with a mix of slow- and fast-chargers – the former being located primarily in residential areas, while the latter is found in service areas. Multiple EV charging point operators (CPOs) work in the same large locations, meaning queues are almost non-existent.

Market share of EVs in the Netherlands

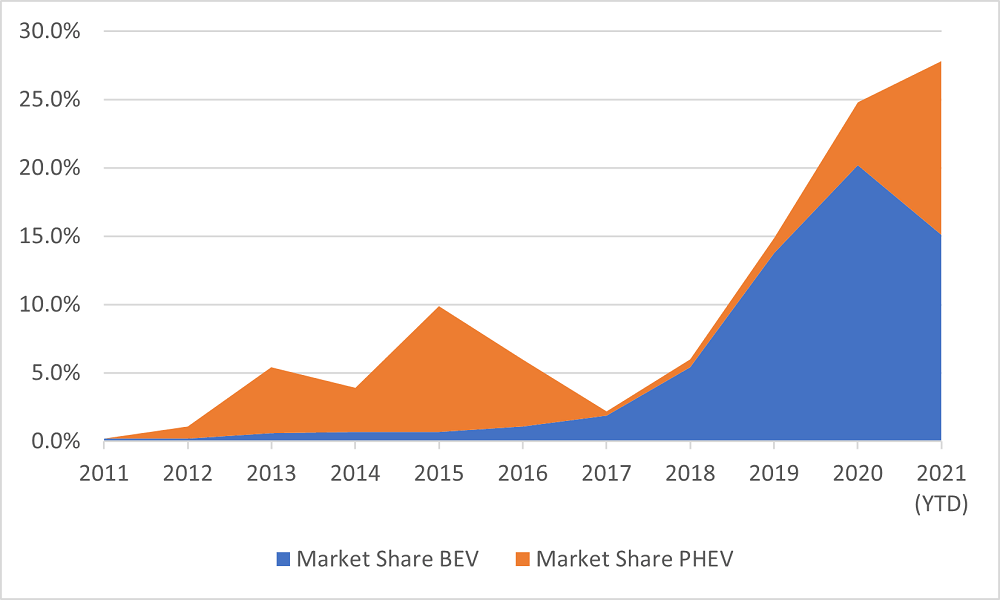

There have been significant fluctuations in the Netherland’s EV market share, moving from a plug-in hybrid (PHEV)-based market until 2016, to a battery-electric vehicle (BEV)-based market between 2017 and 2020. The current market is more balanced.

All these changes coincided with significant changes in incentives, so one can say that the Dutch EV market evolution goes hand in hand with policy changes. This makes the market a case study for other countries on how to incentivise EV uptake.

Varying incentives

The first peak in 2013 coincided with the end of the registration fee exemption on 31 December. This mostly benefited PHEVs because, at the time, fleet managers bought plenty of these models as company cars to access the fiscal incentives. However, end-users were driving them as regular hybrids, and in many cases not charging them at all, because they had free petrol as part of the company-car perk.

After a drop in 2014, the following year saw another peak in sales, mostly thanks to PHEVs. These vehicles had seen their registration fee jump from 4% to 7% in 2016, with BEVs keeping the lower rate.

Still, despite fewer sales on the PHEV side, the powertrain’s overall supremacy did not change in 2016. Despite carrying more registration tax than a BEV, PHEVs still benefited from an exemption of the benefit in kind (BiK) tax, which made them attractive as company cars.

As such, the government again changed the rules for 2017, ending the BiK incentive for PHEVs. The effect was immediate. PHEV sales plummeted while BEVs surged, allowing two years of accelerated growth. In 2019, the BiK exemption ended for BEVs, moving to a BiK tax of 4%, and a price cap of €50,000 was added. BEVs priced above this threshold paid the full 22% tax as applied to regular vehicles.

This resulted in a slower growth rate for BEVs while allowing PHEVs to regain some relevance, especially on the higher end of the market. The price cap made BEVs less appealing compared to PHEVs of the same category.

In 2020 and 2021, a progressive decrease in BEV incentives (in 2021, BEVs carry 12% tax, while price eligibility was reduced to just €40,000) made the market more balanced between both technologies. At the same time, the total EV share continued to grow to the current 28%, thanks to increased PHEV sales.

With another increase in the BiK tax (16%) for BEVs set to happen in 2022, expect another peak by the end of this year. The BiK incentive for BEVs is set to end completely by 2026.

With new and more competitive BEV models set to land in the coming years in this market, BEVs will represent close to 100% of the Netherland’s overall automotive market by the end of this decade. This is in line with the country’s 2030 ZEV mandate effects. However, as demonstrated previously, there will not be a smooth growth rate, like in Norway. Instead, there will be several peaks and valleys that coincide with the incentive changes.

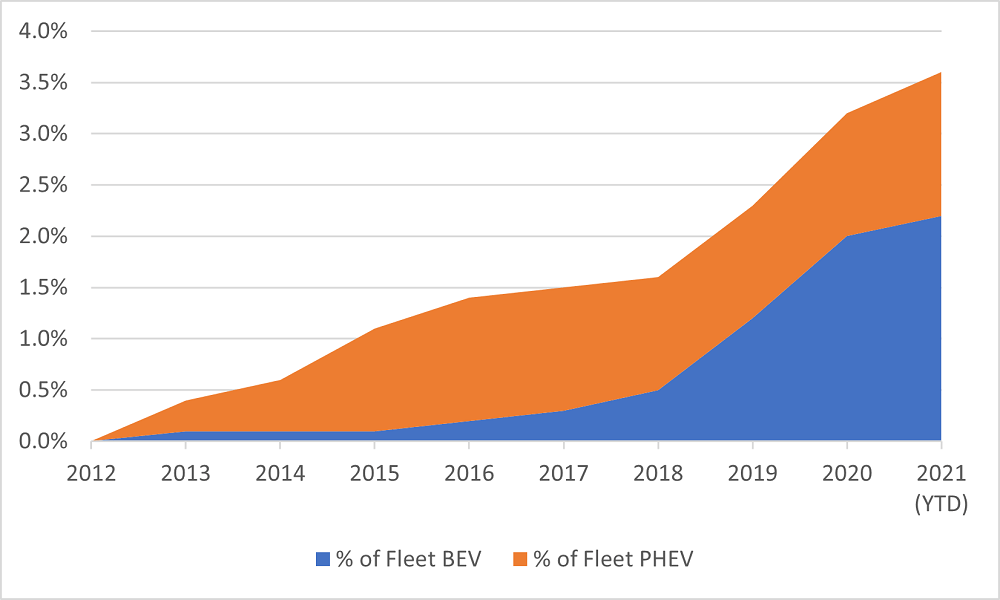

EV percentage of the Dutch vehicle parc

When it comes to fleet numbers, the curves are smoother, with initially strong growth from PHEVs. They hit the 1% share of the total fleet in 2015, stagnating afterwards, while BEVs only reached the 1% mark in 2019, jumping to 2% in the following year.

Still, with the current EV fleet representing just 3.6% of the total numbers and the 100% zero-emission vehicle mandate only set to be enforced by the country from 2030, a complete phase-out of internal-combustion engine (ICE) models is not anticipated until 2050.

Level of BEV incentives

How big are the incentives?

There is a purchase incentive of €4,000 for private buyers, if certain conditions are met. The vehicle needs to be a BEV with a range of at least 120km, while the price should not be higher than €45,000. This incentive is said to be extended until 2025. Registration tax is reduced for BEVs, also benefiting from a lower BiK rate.

In 2021, the only relevant incentive for PHEVs is connected to their low CO2 emissions, which ties them to the minimum tax bracket. Finally, one crucial drive for change is the zero-emission mandate set to start in 2030. From this time, only BEV or hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles will be registered in the country.

Explanation of each incentive

- Purchase tax exemption, purchase incentive, VAT exemption, import tax exemption etc.

- Ownership tax exemption, bus lane use, toll exemption, free parking, free ferries etc.

- VAT exemption, BiK tax exemption etc.

- Charging cost deductibility, special licence plates, EV charger subsidies etc.

The charging-anxiety ratio

EVs do not mean much without a charging infrastructure because, for BEV success, three variables should be met:

- Price should be close to ICE models

- Range should be enough for the needs of the buying public, avoiding range anxiety

- Drivers should have enough CI to be able to charge while on the road, avoiding charging anxiety, something that can be as damaging for EV adoption as range anxiety.

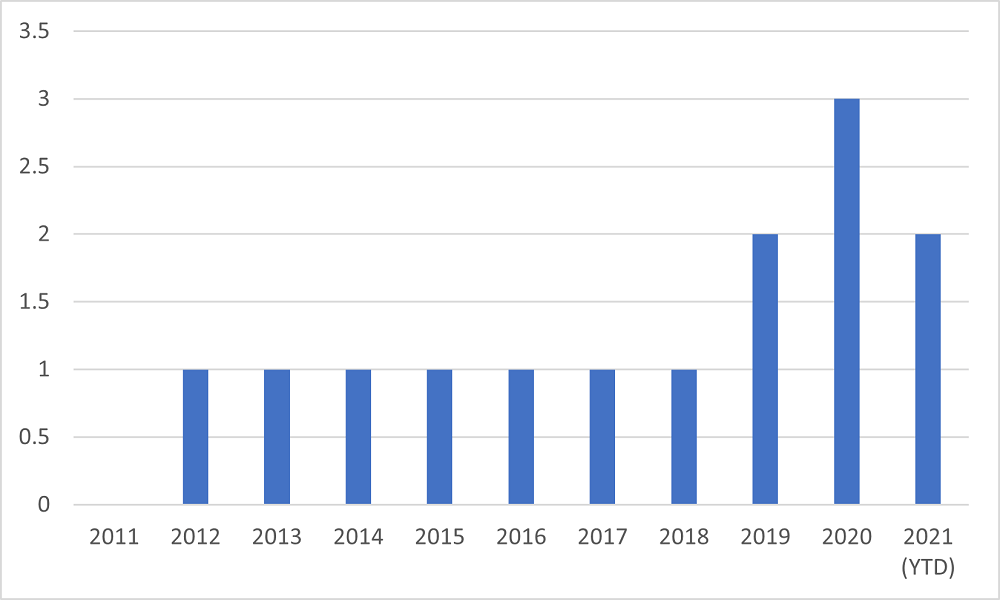

BEVs per charging point in the Netherlands

The same can be said about CI maintenance, the official numbers assume that all EV charging stations are operational, which is not realistic, so the frequency of downtime should be taken into account when designing the CI. The same logic applies to the EV driver, who will need to have a plan B (or even plan C) if the initial charging station is offline.

Due to a focus on CI development, the number of BEVs per EV charging point has stayed roughly the same throughout the year. However, the current ratio of two BEVs per charging point is worlds apart from the 17 BEVs per charging point ratio that Norway, another leader in electrification, currently has.

With such a low ratio, queues are rare at EV charging points, and with multiple CPOs operating in the same service area, it even allows the driver the luxury of picking the one with the most competitive pricing.

Easy charging

Many ask the question ‘how easy is it to charge in the Netherlands?’ The answer is very easy. Firstly, roaming protocols were enacted over a decade ago, which allows roaming abilities for the several operators in the market. So, drivers can charge wherever they like with just one card or app, instead of the multitude of cards that are required in other countries.

Secondly, the slow charging roll-out started traditionally, focusing on supermarkets, car parks, or shopping centres. But with time, local municipalities started to become involved, and if drivers requested EV charging points near their address for roadside charging, they were added to the network. This is a relevant benefit for apartment dwellers who often do not consider an EV because they do not have anywhere to charge.

Regarding fast-charging infrastructure, there are a number of operators in the market, such as Allego, MisterGreen, Shell or Vattenfall. The largest player in the Dutch market is FastNed. Their stylishly designed EV charging stations use solar panels to feed in renewable energy, while their stations always have at least four points that can charge at 150kW rates.

The company already has partnerships with supermarkets and hotel chains and has an ambitious expansion plan inside and outside Dutch borders. FastNed is already present in the UK, Belgium, Germany and Switzerland and is aiming to become the second-largest CPO in Europe, ahead of Ionity and only behind the Tesla Supercharger network.

Overall, the Netherlands demonstrates that fiscal incentives can be formative for EV adoption, but despite not having a great deal of incentives now, a large number of EV charging points available and an absence of charging anxiety has a positive effect. This is allows the Netherlands to continue to be one of the forerunners of EV uptake, despite these lower incentives.

Part one of this series focuses on electrification in Norway.