The race for European semiconductor self-sufficiency

18 July 2023

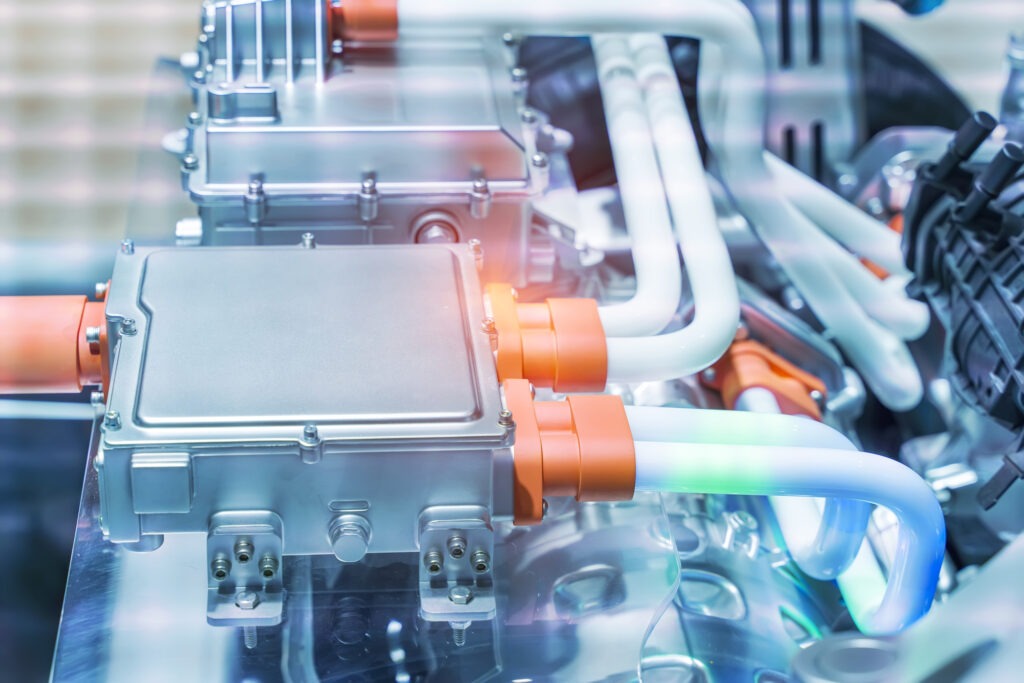

Semiconductors have been a vital automotive technology for a number of years. However, the crucial role they play in both the production and function of vehicles was not fully evidenced until the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in major new-car market upset.

Supply chain disruptions caused massive production stoppages across the world, leading to profit losses among car manufacturers. A recent report from S&P Global Mobility found that in 2021, chip bottlenecks resulted in the lost production of some 9.5 million light vehicles.

Since then, automotive companies have created strategies to secure future chip supplies. At the same time, technology companies have announced plans to ramp up semiconductor production. But is this enough to safeguard against further disruption?

Chip demand to triple

According to industry analysts, European semiconductor self-sufficiency will continue to fall until 2030, even when accounting for planned projects to build fabs. This comes against a backdrop of rising demand, mainly driven by the rise of electric vehicles (EVs), autonomous driving technology, and connectivity.

Germany’s automotive association, the VDA, pointed out that globally, the sector’s required share of chips will increase from about 8% in 2021 to 14% in 2030. Meanwhile, global automotive demand for semiconductors is expected to triple by 2030, from around $50 billion (€46 billion) in 2021, to approximately $150 billion by the end of the decade.

The VDA also expects European companies to become more dependent on foreign supplies unless further measures are taken to accelerate investment in semiconductor fabs on the continent. The EU has taken steps to lower this dependence, hoping to turn the region into a major global semiconductor player.

The bloc’s proposed Chip Act aims to more than double the EU’s share of global semiconductor production from around 10% to 20% by 2030, with the Commission planning huge investments. Overall, more than €43 billion of policy-driven funding will be dedicated to support the Chips Act until the end of the decade.

China export ban

Recent news out of China has, once again, highlighted Europe’s reliance on international supplies. The country announced plans to restrict the export of gallium and germanium products – critical metals used in semiconductors.

Volkswagen (VW) told Autovista24 that it is continuously evaluating and monitoring the situation and its potential impact. It recognised that gallium and germanium are important resources for automotive products, especially EVs. Other European carmakers have been more outspoken. When approached by Autovista24, Stellantis referred to a recent comment made by its CEO Carlos Tavares.

Tavares argued that restrictions on gallium and germanium exports should not force Western companies to disengage from China as this would not be realistic, nor would it be in the interest of those companies. ‘We are not in a war with any Chinese suppliers. In this case, it is up to the European Union to collaborate with Chinese authorities to find a solution,’ Tavares said.

Renault chairman Jean-Dominique Senard was clear on the matter too. In an interview, he said these recent developments have emphasised Europe’s over-reliance on China and the pressure to build a costly supply chain.

‘We are capable of making electric vehicles, but we are fighting to ensure the safety of our supplies,’ Senard said.

Crisis looming?

While China is not the only producer of gallium and germanium, the country is a dominant supplier of the metals. Around 80% of gallium production takes place in China, according to the Critical Raw Materials Alliance (CRMA). The nation is also the major producer of germanium, responsible for 60% of total production.

Does this mean another supply crisis is looming? It is currently unclear what the Chinese restrictions might mean for the chip industry, but gallium and germanium are hard to replace. Looking for alternatives would be an option, albeit a time and cost-intensive one. The ban will likely cause another headache for the automotive industry, especially as the restrictions are set to come into effect at the start of August this year.

The Federation of German Industries (BDI) said that the ban illustrates the urgency for Europe to quickly reduce its dependence on critical raw materials. As part of Europe’s Green Deal Industrial Plan, the EU has proposed a set of actions to do so. The Critical Raw Materials Act seeks to brace European industries from further supply disruptions.

Still, complete self-sufficiency will be unlikely, and Europe will continue to rely on imports. In light of China’s export curb, raw materials partnerships, free trade agreements, and attracting drawing businesses to Europe, will play an even bigger role in the future.

Chip investments

Meanwhile, Stellantis is taking matters into its own hands. The carmaker recently formed a joint venture with technology manufacturer Foxconn, to design and sell state-of-the-art semiconductors. These will be supplied to the automotive industry, including Stellantis brands, from 2026 onwards.

Dubbed SliconAuto, the venture will offer an auto-centric source of semiconductors for computer-controlled features and modules, particularly those found in EVs.

‘Stellantis will benefit from a robust supply of essential components, which are critical to fuelling the rapid, software-defined transformation of our products,’ said Stellantis chief technology officer Ned Curic. ‘With this joint venture, we can create purpose-built innovations with an efficient partnership.’

An increasing number of carmakers are signing direct agreements with chip providers in a bid to strengthen their supply chains. One example is Mercedes-Benz, which has partnered with US technology firm Wolfspeed, to deliver silicon carbide chips to the premium brand. These will feature in the carmaker’s next generation of EVs.

Wolfspeed itself is planning to construct the world’s largest manufacturing site for silicon carbide devices in Germany. It will be the company’s first fabrication facility in Europe and will support the growing demand for automotive semiconductors in the region.

Germany leads the way

Germany is turning into a hotspot of semiconductor production. Infineon, one of Europe’s largest chip manufacturers and suppliers, is pouring billions into a new site in Dresden.

Intel is also investing billions in a European semiconductor ecosystem over the next decade. This will cover the entire value chain, including research and development, manufacturing, and packing technology.

Last month, the company announced an investment of more than €30 billion in Germany, to expand its manufacturing capacity in Europe. Intel said this would help the EU advance its goal building of a more resilient semiconductor supply chain.

It also plans to build a ‘leading-edge’ wafer fabrication site in Magdeburg, Germany, with Chancellor Olaf Scholz calling the move ‘good news for Germany and for all of Europe.’ Additionally, the US company is spending around €4.3 billion on a site near Wrocław, Poland, to create a semiconductor assembly and test facility.

While these are all promising developments, these chip facilities will not begin deliveries until the second half of the decade. Europe has no choice but to continue investing in semiconductor production, but minimising its dependence on other countries is going to take time.